Nadiah is the Founder and Programme Director of Klima Action Malaysia (KAMY), a climate justice and feminist organisation. Nadiah contributes her climate crisis, gender and Business and Human Rights (BHR) policy expertise to think tanks and global councils, authors key environmental rights reports to help shape climate governance with a human rights based approach. She was formerly attached to Institute of Strategic & International Studies Malaysia, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, European Climate Foundation, Stanley Center for Peace and Security, INGKA group’s Young Leaders Board and the Swedish MFA international advisory group for the environment, climate and biodiversity.

*Photos provided by KAMY.

Tell us a bit about your current role in the civil society space.

My name is Ili Nadiah and I’m the current Programme Director of Klima Action Malaysia (KAMY). Right now, the kind of activities that we do within KAMY is doing climate programmes and we seldomly do direct action anymore. Most of our programmes involve research around policy, climate governance, building capacity of stakeholders like news media, journalists, editors, Orang Asli, young women. The other part is the outcomes from that. The research will culminate in policy advocacy, lobbying. The last programme that we think is really important is on coalition building, so we build a lot of networks and coalition with other groups because we know that climate change is not something that an environment group per se [can address alone]. We need a lot of different perspectives, people with different backgrounds, from different social backgrounds, people with different courses to come in to speak about their experience and share what’s happening on the ground so we get a clearer picture. Those are some of the main programmes that we are doing.

Tell us a bit about your personal background. Did you grow up in a particularly political home?

No. I grew up in a very middle income family. My parents are from different regions in Peninsular Malaysia. They got married and resettled in Kuala Lumpur where I was born and went to school over here. I never had any inclination towards activism, no idea what the hell it means actually. I think my first brush with activism or that form of rebellion or opposition was during Anwar Ibrahim’s exit from the government in the 90’s. I think that is the first time when I saw what was this all about? I remember during high school, there was a lot of discussion among school teachers at that point. Should we talk about this, should we not talk about this, maybe not talk about this because we are civil servants. So that was the first time I thought wah, this is like a subversive thing that’s going on. That is my earliest brush with these kinds of issues face to face.

But there are those larger ideas that come through during 90s, especially the idea around South Africa Apartheid. We learned that at school, and then the Occupation of Palestine and things like that. So these are some that really formed a lot of my opinion about the outside world, and that was also the time when you have the wars in Serbia. A lot of my information about outside world came from this information like, people are warring about religion, about oil, about everything. But then I never make any informed decision to actually do activism. I thought that okay, I’m just going to do like what my parents do. Go to work, get a cushy job and raise a family. But that all went to the dumpster when I went to Germany for my undergraduate.

Climate Rally on 7 July 2019*

Where did you hear about the war in Serbia and the Apartheid?

From television, from newspapers, those are the two main things. And then, from school. I think at that time, people are doing a lot of donation against war. There was also the time in the 90s where there’s a famine going on in Africa. So I grew up in the 90s, I was just maybe like, seven or six years old but there are songs that explain this, right. Like contohnya, lagu-lagu daripada Zainal Abidin. So I think people who grow up in the 90s are quite aware because the way that information have been passed to us are very direct. You have no other sources. Today we have a lot of different sources, a lot of different narratives, right? So I would say the indoctrination happens quite fast lah, people would understood issues and things like that. When I left to go to Germany to study, that’s where my world view changes.

Where in Germany?

In North Rhine-Westphalia, several cities. Cologne, for example, is an old city, but it’s vibrant with young voices. There’s a lot of migrants, and there’s a lot of angry migrants and refugees. I remember when I was first at the university, my first friends were not Germans but I have Syrian friends, Iranian friends, which was surprising that they both talk to each other given the fact that the Iran–Iraq War happened in the 90s. I remember there was a makan-makan at university and we have these two groups coming in, and then they were talking about it. I came in as a third person. They openly talk about what happened to their families and these Iranian students were talking about what happened to their families, they were exchanging experiences and they were both you know, musuh lah. Enemy on the frontline at that time. So very open and very forgiving, in a way, and I was just like man, I’ve never seen that in Malaysia because we don’t have a lot of refugees and things like that back then. I mean, I’m not exposed to that within my family or my environment, so that’s where I realised that there are people who facilitate this kind of discussions, people who facilitate this kind of peacebuilding, and then that’s where I began to know about different social justice movements.

I think I was mostly close to the people who run the Kurdistan liberation movement. There’s a lot of things that happened in Germany at that time politically. The leader, Abdullah Öcalan, was captured and then there was a lot of uproar of Kurdist refugees in Germany, and they are really strong movement of women. I remember that I don’t understand much about the issue around it, but I just wanted to know how is it like being in that situation where you just got plucked out from your country and then you have to make a choice to leave your country. That is a huge decision. And you as a woman, how is it like moving in such a movement. The Kurdish movement is not quite a peaceful movement, they carry arms tau. So I learn, I listen, I think that was the part where I got my second enlightenment about life and I think oh, life is just so in a mosaic. It’s not like you get a cushy job and then that’s it, you know. So many things are happening, so many different people with different views, I think I got a culture shock when I went to Germany.

First time that I went to one particular class and there was like a congregation of people, and then I get to know what the others are studying. It was like orientation week and a person in front of me told me she studied pedagogy, and for the love of my life, I have no idea what pedagogy means. I’m like, what is that? Oh, I study language. I was like, German language? She was like, yeah. So I was thinking wow, people are actually studying literature and things like that. I as a scholar, got scholarship from the Malaysian government, was living under a tempurung. I didn’t know that people can study languages, people can study [language pedagogy]. I know that people study literature, but pedagogy is slightly different and I was so surprised that when I asked, everyone had the choice to pick what they want to study. They had a passion in it. I was just there because I got really high marks and then I passed the interview and the government said kau study electrical engineering and that’s it. You never question why and I was just that kind of person. Then slowly after that, I get to know how life was for different people and I think Germany is really a great melting pot. So that’s where my inclination towards social justice movement started.

So you studied the natural sciences. Did you get the chance to take social science or humanities courses?

No. In Germany, I studied engineering so no. It wasn’t encouraged.

Could you describe a bit about the kind of protests you attended or were involved in back in Germany?

It was vibrant. This is a really sensitive topic but back then, the anti-fascist movement is not like what you see today. Now, it’s like a mix of black bloc and everything. Everyone is getting money from somewhere lah to do their propaganda and stuff. But I remember that I joined a protest in Düsseldorf once and it was very vibrant. People are playing music, people are cooking for each other on the streets and of course, you would have the neo-Nazis coming in from the other side, police is blocking them. You always have those scuffles at an antifa [rally]. The word antifa is a very scary word I think, across people right now but they were peaceful. Lately, there has been a lot of infiltration and all this kind of stuff, but it all started from there for me.

Do you know which year that was?

That was in 2009, before Occupy. It was a quite liberating experience to see how peaceful (it was) and the sense of community, everyone’s love for each other, every different gender was there. You come to a Kurdistan protest for example, you can still bring your rainbow flag, your purple flag, whatever flag you can as long as it’s a peaceful agenda. I think I participated in some of the activities like cooking for refugees who were also protesting and marching, and then doing some artwork, designing posters, printing them. There’s some few safe houses in Düsseldorf where we come in and discuss, but I was doing it in a very subversive way because I’m a Malaysian person, so I have to be really careful. But then it was really nice, it really changed the way how I think of protest. I mean man, Germany has really a lot of different protests and also in France, I’ve been in France as well. The geopolitics and the history of these two countries is very much different, and the protest in several regions in Germany a bit more aggressive as compared to certain areas.

The ones that I’ve seen yang macam sangat aggressive are the ones in Berlin, in the northern part, oh those are really… I never got stuck in one, but I have some friends who were stuck in one part where the black bloc actually comes in and there was a lot of police brutality. Oh the police brutality, I tell you man. Really brutal. German police, we call it “Bulle”. It means the bull. So they are really aggressive man, you get really scared. But then people are aware of their rights, people know what their rights are if they get police brutality, intimidation. People who go to protest, they learn all this. They basically have a group of people who teach them. Something like what SUARAM (Suara Rakyat Malaysia) constantly doing: teaching people about police brutality, how to act, how to do protest and things like that. But then the level of acceptance of people towards protest in Germany and France, it’s a common thing. People are like okay, I support you guys. But now it’s really bad lah, particularly in the UK. Just Stop Oil, for example, have been viewed as militants, eco-terrorists and all this kind of stuff. So that’s some of my experiences, of seeing things, experiencing things back then. When I went back to Malaysia, I didn’t do protest but I start to engage with communities in Malaysia, I came back maybe in 2016 or 2017.

I wanted to ask a few things about that one. Did you think these protests were effective in getting their demands or do you think there was another purpose to these protests that you attended?

I think the purpose of the protest: to raise visibility about the issue. Because the German media like (Der) Spiegel, (Süddeutsche) Zeitung, they were very pro to a certain political party punya alignment who was anti-refugee, anti-migrant. So they would post things that are not reflective of the situation on the ground, trying to find scapegoats and things like that. These are things that are happening right now, of course. It’s becoming more worse than before but back then, it has already started lah. They would blame migrants like Turkish migrants. Germany has a lot of Turkish community, first and second generation.

On the issue of safety, who organised the training and did the training you received in Germany help you feel more confident or safe in protests?

There’s a lot of groups. They are collectives. They tumbuh macam mushroom and then it’s gone, dismantled just like that. Dia sangat dynamic. You wouldn’t see a group like SUARAM, 20 years still a group. So these are small collectives, dia bangun dan dismantle, bangun dan dismantle, and they are okay with it. So they muncul maybe at a certain junction of the time where we need people to do this for protest, and then suddenly there’s a collective of people supporting each other, bringing food, bringing all these different kinds of resources. Then after the protest has ended or they reach a certain target, you dismantle and that’s it. And everyone’s okay. That’s where I realised that KAMY should have a expiration date.

Why did you decide to do the climate march and how did you get it going in the first year?

It was 2018, the latest IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report came out at that time. I remember I was at my university in [Malaysia], it was my second degree. We had a discussion about it because I was studying environmental science, so it’s very different than what I did before. It was engineering and now I’m studying environmental science so I’m like, patah balik sikit. Engineering is solutions, so tunnel vision, but then environmental science is larger so there’s more encouragement to study about policy, governance, other social aspects. Engineering is so techy, but it gives me a great perspective of things. I understand how engineers think about climate solutions, how science people think about solutions, very different.

Coming back to the question, so there was a class and we were supposed to discuss about the findings of the 2018 IPCC report. I remember the feeling of the room is dead. Everyone is like, is this really happening? What are we doing about it? Nothing is moving, the needle is not really moving. We were all worried and then we were looking at videos of this school kid in Stockholm doing strikes and youth around the world. They galvanise movements to go down on the street and demand for something better for climate. We decided like eh, why not we just do something? We didn’t even thought about oh, let’s do advocacy first. Let’s just go on the street because there was a lot of noise, a lot of visibility around climate from the protests being done by Greta (Thunberg) and then some other countries after that around the world.

Global Climate Strike in March 2021 (Source: KAMY Facebook page)

Which year was that?

End of 2018. Kemudian in 2019, it reached a peak of all strikes everywhere so we decided let’s just take this opportunity to piggyback. We decided let’s piggy back on the visibility around the world and let’s try to bring this visibility to Malaysian people. What is happening globally elsewhere is also happening here, but we were so naive at that time. That’s where we met with another KAMY member, Aroe (Ajoeni), some few other people who has no clue about doing climate protest but we wanted to do it. So Aroe did the first climate protest. She wanted to do in front of her university and then dia kena intimidate lah daripada school, daripada university reps and stuff like that. They designated her to go to bawah jambatan and she with her 25 other people who brought the banners was standing there with their banners about climate emergency. And then, she needed to go to the balai polis and the thing is, no one wanted to company her, so she went alone. And she has no clue about safety, nothing. She thought like okay, we tell police yang kita orang nak berkumpul dan berlega di kawasan sekian, sekian and then the police said apa yang kamu nak buat? Pastu she got really scared. She said okay, saya nak inform saja and she thought that was it. She didn’t have any clue about PAA (Peaceful Assembly Act), nothing, zero. She thought like okay, Greta can do it, I can do it, so let’s just do it.

It started from there and then I met with these people, and then we started to get serious. Okay, if you want to do protest, let’s get ourselves educated about safety around this, this, this, so that’s what we did. That’s why I know Fitrah (Marican) from Dapur Jalanan. I think she is the glue lah to a lot of things because she is connected to KBU, which is Kelab Bangsar Utama so they have the space, which they share with Dapur Jalanan. That’s where I start to know people who did the protests in 2018 like Lawan Najib. They’ve done protests before, so I engage with them and they teach kita orang macam mana nak buat protes, apa taktik you kena pakai in Malaysia. None of us had any exposure in doing things in Malaysia, so we don’t know what are the akta related to it, what happens if polis ambik you, is there a permit, no permit, what is actually a permit, actually permit does not exist all this kind of stuff, so we had all the learning. So it started from KBU and people from Dapur Jalanan, and then people from SUARAM Pastu kita orang discuss lah macam mana nak buat ni, kau datang lah ajar budak-budak kita orang, and then there was a point where we had strategy meetings about how to become negotiators, how to find people to do [first aid]. We were kind of prepared on that lah. So our first protest, there’s actually more police than us and they were like oh takde lah, ni kumpulan-kumpulan biasa. We didn’t even send anything, no notice, nothing. And then the second one, we send the notice and then they responded to us. We did a couple few of protests. It’s not a protest lah, it’s a march.

Prior to your first time organising a protest, did you attend any Malaysian protest after coming back from Germany?

I attended a protest tapi I wasn’t organising. May Day, because I was part of the anarchist punya [collective] kan. May Day, Tangkap Najib. Women’s March pun ada.

During those protests that you attended, did you feel that the atmosphere was different than in Germany? Did you feel a different level of safety here as opposed to in Germany as a protest participant?

Well in Germany, the perasaan tu a bit heightened because I pernah eh kena (dengan polis). They called me in dekat balai polis, we all got into a single truck and then dia mintak I passport. Pastu I kata I tak bawak passport, so my friend had to drive around 2.00 am in the morning to go to my place, pick up my passport. Nasib baik dia ada kunci. So at that time, I was scared lah. Eh, jangan lah bagitahu dekat Embassy and whatever. So they were just interrogating but it was scary because if they notified the Embassy, then bye bye, adios. So it was scary. But in Malaysia, the fear comes from a different place. It was kinda like we had a tyrant. We had Najib Razak, the tyrant and he was silencing everyone and mobilising the police.

What did you think was the worst that could happen to you?

For Najib, I think the worst is either they use police brutality yang boleh membawa kepada kematian, or forced disappearance. But I don’t think I’m those kind of people, they would definitely focus on PSM (Parti Sosialis Malaysia), people who are the organisers. But then as you march together doing the protest tu, you felt that if something happens to me, then somebody else would know what would happen to me. So there was like a sense of safety lah around those areas. But then we didn’t go to any training, there wasn’t any. People just came in droves because people were angry at Najib.

And then, Women’s March is also fairly different. I remember the one that I went to in 2018, one of our friends, her car was smashed by a brick. She was one of the organisers, and she was scared of carrying her LGBT identity as publicly as that. She was doxxed online, people fat-shamed her, so many things. I haven’t started on the digital part yet. Digital part is also another form of new frontier kan where people protest.

Could you go deeper into that? Like what other forms of tactics are there besides breaking glass?

Masa protes Lawan tu, we were the organisers kan. Kita orang try to maintain uniformity. Everyone setiap satu meter ada benda macam ni, supaya kita tak kena label by the government as oh ni lah budak-budak yang protes ni, dah lah tak jaga social distancing, blah, blah, blah. So we really, in all of that, want to get it as perfect as possible supaya we don’t get that flack. But then, I knew that some people will come to break that rule. They think that why you guys doing this so uniform? This is the time where we need to disrupt. And then they datang from belakang and I jaga kat belakang time tu. So I nampak dia orang. We know that they’re going to steal some shit dekat depan, and they did. They got the press to cover them. They wanted to break the mold lah, like protest is not just about sitting down peacefully. That you have to use the space, whichever space that you have claimed to speak, and then they did that. So a lot of people were thinking who are these youngsters, why are they disrupting the Lawan protest? And there were some few camp that said that. So we’re like ala biar lah, dia orang ni tak tau ada banyak form of protest dekat Malaysia. So yeah, that was it. I’m so glad that I know some people back then, because the world is completely a different place then.

Let’s zoom back to that first protest you organised. You were describing talking different people in preparation for the day, so can you continue on that.

I remember that not a single environmental group engaged with us on the first protest and I think people were quite unsure, scared. It’s just I felt that because we came in as a nobody, we are not under WWF (World Wildlife Fund), nothing. We just [appeared and] we were there, a collective of young people.

At that time, KAMY was a collective?

We were just a collective, we weren’t a proper group. Like people come in and out, but we have the core people who do things. It was a different time back then. There wasn’t any participation or engagement with any environmental groups, and I think they were quite unsure who we are. They are also scared like, why are you going on the streets? Why don’t you speak to the government first? They have a different perspective lah. And then we just tak apa, we just go ahead. At that time, we were discussing dengan another collaborator, all these people who organised the Tangkap Najib protest. Just go ahead Nadiah, just do it. Lantak lah all these big groups, just do what you think is right. And then we were discussing, okay let’s just do it. We got cold feet lah at one point because we didn’t get any support from environmental groups. Like, where were they? The one that is helping us is KBU, Dapur Jalanan and all these grassroots yang do protests, SUARAM.

Climate Rally on 25 May 2019*

How many people came for the protest that day?

I think less than 100, but then there were more than 50 police. The ratio is maybe dua orang, satu polis macam tu, 2:1. It’s just police like Special Branch and all this, but they were equally surprised in that they don’t know who we are. Ada one polis tanya kenapa kamu kena turun marching, rally sana sini? Kenapa kamu tak pergi sungai kutip sampah?

Right, that’s their idea of environmentalism. So were there any issues during the protest?

Nothing, surprisingly. Everyone thought okay it’s a peaceful thing, the police saw we didn’t do anything, kita tak keluar ayat-ayat yang [menghasut] and it was just our first protest. And then we built up our narrative with second and third, and then we got into problem lah with the police and they kept asking us to go to the police station to give statements for the next few protests.

Did you have to give statements for the first one?

The first one, takde. Nothing. It was clean and we like, built our confidence. We were so confident we can do the next one, oh let’s plan the next one real fast.

Did you invite media to the first one? Did they cover it?

Yeah, I think we did. They cover.

Do you think they covered it positively?

It didn’t go to the first page or nothing like that, tapi they weren’t asking us the right questions. I remember this. That’s why we are doing the Lensa Iklim programme, we want journalists to ask us the right questions. They were just asking like adakah anda fikir anda ni Greta Thunberg? Questions like that you know and it pisses me off when I think about it. So we thought that ala, the narrative of the media is not going to change much lah so we tried to build our capacity for the next one.

So that first one was the end of 2018 or start of 2019?

Start of 2019.

When was your next one?

I remember in July, we did once. September, we did once. We also helped other protests. We helped support the organising of the protest, Penang Tolak Tambak in front of Parliament in 2019. Sebab we all participated in all these protests just in 2019, 2020 kan COVID. There was also a protest at Padang Merbok pasal Orang Asli, we were there to give a speech. I actually drove from Gua Musang, Kelantan that morning to come to that protest. What happened was we were helping lah this other protest to organise, teach them about safety and things like that because they are also like us, collectives. Penang Tolak Tambak lagi lah, komuniti kan. But then they were backed by Sahabat Alam Malaysia, that time was already big, and CAP, which is the Consumers Association Penang. So they were already quite established in Penang and when they come into [KL], they just wanted to get logistical support, visibility in Klang Valley people and things like that. So we try to pass on information lah, how to do protests to others.

But then for our own protests that we organise by ourselves, there was also a sizable amount of people within the environmental groups call us and ask us to quit. They said that we are polarising people. Protest is a very aggressive move tau sebenarnya, and it’s not even a protest, it’s a rally. Tetapi Malaysia space, when you talk about rally, it always has a negative connotation. People think you just come in to disrupt and shit. And these environmental groups, they already have build bridges with government, they already have good rapport, and then now we come in and they say that we are destroying good rapport with government.

Climate Rally on 7 July 2019*

Even if they didn’t work with you?

No, we were just newcomers, new kids on the block and they felt that sepatutnya, sebelum you buat protest, you kena engage dengan kita untuk tahu apa yang kita sudah lakukan. That is something that we learned the hard way, because now we are in the same position. (They said) jangan buat lah protes and we still wanted to do it because we think that we are building momentum, we are getting visibility. Some of our protests got into the front page and some journalists were asking the right questions, and then some politicians also came in. These are protests that we are doing in 2019, it’s a honeymoon period for the PH (Pakatan Harapan) government, right? So no one is doing protests, and suddenly there’s an environmental group doing protests in that year. It’s just great lah to show that we want more accountability. Now that PH government is there, there should be more accountability. Tapi of course lah change of government suddenly after 20 years or something like that, but we just wanted to give visibility and then for people to ask the right questions.

We engaged with SUARAM, all the grassroots, which are also key stakeholders when you talk about climate action in community level. We build up from there, so that’s what happened. I think we sort of built this kind of support from other environmental groups after that in our last protest. Suddenly, there was a lot of people who came in.

So the addition of new groups happened by the second protest?

The third protest in July. That was even bigger than the second one. The biggest one is in September.

Climate Rally on 7 July 2019*

What did you do to change their minds?

I think we sent the right message. Before this, the messaging wasn’t that clear in terms of why we are doing this. Are we calling for climate action in Malaysia and globally? Are we like, marah government in other countries in the Global North? Adakah kami marah dengan kerajaan di Malaysia? So during the first protest, we weren’t quite clear.

Was this before or after the popular usage of climate emergency started?

This was during the second one. I think the strongest, clearest call that we use on darurat iklim was during the third and the fourth, which is in July and September. So that’s why we use darurat iklim. A lot of people don’t agree with this, they say kenapa guna perkataan darurat? We had a lot of discussion on that because they felt that perkataan darurat tu terlampau extreme. And then true enough lah, now we are living in the extreme. Back then, people don’t want to believe but yeah, here we are. Perkataan darurat tu, people still think about the Malayan Emergency. It wasn’t the most popular usage lah, it comes with the negative connotation kan but I think people start to understand during the third and the fourth strikes. There was a lot of environmental groups that also came in to support. We have Greenpeace coming in to support, people from WWF (World Wildlife Fund) as well came in tapi bukan sebagai organisation, as individuals. And then Fahmi Reza was also there with his banner.

It’s great to see people, but I think the reason why people were on the streets in September 2019, because there was haze. Time tu ada haze yang teruk kan, so we had to change our narrative a little bit there on how to link climate and pembakaran hutan. There was the intersection with corporate accountability, so our banners are all tangkap syarikat, jerebu, blah, blah, blah, so people were really angry because jerebu is a 20-year-old problem. I remember that we did die-ins around the city. So basically, we go to a certain space and then we lie down in masks, pastu hold protest signs, and people were asking us questions. We were just trying to gauge the temperature so we did it in KL Sentral, we did it in KLCC, we did it in places where there’s a lot of people congregating. In hot places like this, you have bukan saja police bantuan, police yang anti-terrorism tu semua ada. One of our members was pulled in by one of the police in KL Sentral and we had to reason with the police to release our member. I said that abang tak nampak ke jerebu? Kita orang protes untuk memberi kesedaran tentang jerebu. Abang pun, saya rasa, membesar zaman jerebu dari dulu sampai sekarang, so kita bukan buat apa-apa yang menentang. Kita cuma memberikan kesedaran. Lepas tu abang tu was like okay, saya faham dik. Jerebu memang teruk. Suddenly he was like talking about his time because he is a police officer and he has to always go outside kan. Dia kata saya pun dah pening kepala tiap-tiap hari bau jerebu, anak saya dah sakit, he was talking about that tau. Pastu I was like okay bang, okay bang. Abang boleh tak bebaskan kawan saya? Okay saya bebaskan, tapi jangan lah buat lagi macam ni. I said okay.

People are angry, even the policeman understood why we are doing it. But he was just doing his job. When we were at police station pun, some policeman actually understood why we are doing it, but they are like the higher level officers. I remember I came into a room, there was like 12 [officers]. Ada Ketua Special Branch, Ketua Polis Dang Wangi, ketua polis ni, they all come in with their camera, I was being interviewed. This was before the third protest in July. Before we held the protest, they called us in to give an interview because we sent a notice, so they want to know what it’s all about. The lawyer of the police said kenapa kamu nak buat protes? Baik kamu kutip sampah ke, bersihkan sungai, bersihkan sampah, ni lagi bagus. That’s when he made his really amazing remark where I was just like wah, I really need to do more [awareness work]. He said tengok Arab Saudi tu, 40 darjah Celsius dia boleh hidup lagi. Kenapa kamu nak cakap Malaysia tak boleh hidup 40 darjah Celsius? I don’t know whether he’s doing that on purpose, but I remember the OCPD (Ketua Polis Daerah) said that anak saya pun dah banyak cakap pasal isu perubahan iklim, pastu [the lawyer] was like oh okay.

So the interview, they just wanted to size us up. Wanted to know who we are, how many people, are we getting funding doing all these protests, who pays you, all these questions. I was like oh, saya rasa soalan ni tak relevan, saya tak boleh jawab. Rasa macam bagi statement pulak kan? And I was there without a lawyer. I thought it was just a [normal interview], tapi they were collecting video so I’m scared that it will be used against me. Eventually after the protest, they still called us in to give statement. At that time, I came in with lawyers lah, but it was okay. I was just like kami akan menjawab di mahkamah, that’s all. It was really awesome to know the lawyer punya circle that is like okay let’s do this, we will cover you.

At that point in time, what kind of resources did you need for these protests and where did you raise them? Because it was a very short period of time and you didn’t have a bank account then.

We all used our own funds. So we collect, derma, kita ada buat pre-activities. Macam contoh, kita ada buat discussion and then watching documentary on climate emergency in Malaysia Design Archive. They gave us the space, so a lot of people came in and then people donated. And we sell t-shirts, I forgot we sell t-shirts. So we don’t get any funds from outside Malaysia at that time, we just collect through donations and things. A lot of people gave their spaces to us for nothing, like we don’t have to pay.

Did they offer these spaces off the back of that first protest or was it later?

After the first protest. After that one, some people just came in and said hey, I’m going to donate you this much, this much, or you need food or art supplies? People came in for us so I was quite surprised. Yeah. Wasn’t that bad huh? But then if kena masuk [lokap], kalau nak bail and things like that, we weren’t prepared, but I know that people would raise something for us. We already had some few discussions kalau siapa-siapa kena tangkap, kena bailout, they already have a team all prepared.

Nadiah speaking at the Climate Rally on 7 July 2019*

How many people were incoming in 2019? At the height of it, how many, the low point, how many?

People come in and masuk, keluar, masuk, keluar. 15 to 20 at the height. At the low end, paling-paling pun sembilan, lapan orang. This was core members, many of them university students, young professionals.

What were the discussions around the choice of tactics? Because a rally is quite a popular one and you also did the die-ins, so what were the types of protests that you discussed and what were they informed by?

We saw die-ins happening in other countries, I can’t remember where it came from. South America, some youths, I can’t remember but Latin America lah. Because there are also quite a strong presence of climate movement over there, especially from Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Mexico. When we all first came in, we were looking at the global movement. We thought who are the people that we can engage with? So these are after the strikes lah but before that, we just look at them as wah, they are doing this. Let’s try do die-ins. I think we did that numerous times in Klang Valley, so we go over to places where there’s a lot of movement of people macam KL Sentral, all these key places where people would stop a little bit and ask questions. So we sediakan pamphlets, we train our team. We have a die-in team. People who will hold pamphlets, give out pamphlets, explain to people, watch out for any police, there’s a whole thing to it.

But we started doing that and then people ask us the most bizarre questions, but these are legit questions. At that time I was thinking kenapa orang tak perasan benda ni? And we were so naive, we thought people see things clearly as us. We were so wrong, so that’s why KAMY is the way we are today. We think that people’s awareness was just so low, people don’t understand that the floods they are seeing are all related to poor governance, related to climate change which is also poor governance punya problem. People could not make that connection. So die-ins, rallies, those are the two main ones.

And then in our protest, we try to give a lot of space to communities to speak, so we have arranged for Orang Asli people to come in to explain. For example, we call Mustafa dengan Dendi daripada Gua Musang, they experienced the banjir in [2014], the bah kuning in Kelantan. So they experienced this, and the things that they say freaking resonated with everyone, man. Like I remember Dendi said during the protest dia tak buat benda ni untuk orang kampung dia, dia buat ni untuk semua orang. Tak kisah kamu orang Melayu, orang Cina, orang India, kami nak selamatkan hutan ni bukan untuk kami saja, tetapi untuk semua orang. Masa banjir tu, air datang daripada kawasan mereka because the hutan in their areas is gone. So they understand this, they see this, they are the front line of this destruction, so they came out to tell us that.

So that really shaped KAMY as it is today, because we know that we could not move anything forward without getting perspectives, views, active participation from people on the ground, the community, the frontlines. I think those are really our strong core that shape us today from that protest. Because (compared to) other protests, the narrative from climate was different. It was very urban. You don’t see Orang Asli, communities from B40, people from the disability movement, people from gender justice movement speaking about climate, you don’t see that. But now, we are slowly seeing this. You just need to build capacity, build the bridge and then people would slowly step up because they are experiencing this shit, right? I think that’s the thing that we learn a lot from our protests, that you can never move things around if you don’t include people and grassroots. You can’t.

Your 2019 days, you were so involved and you had to do all the different categories: logistics, content, security, social media. Do you think that trained you quite well for whatever you were going to do in Lawan?

Yeah, I was pretty much confident that we can do it lah. So whenever people have reservations, I would come in and say it’s okay, we can plan for alternatives. So we seek for other alternatives. Because we think that at that time, Lawan is a needed voice during COVID-19. It’s a freaking needed voice.

What do you think the impact of your 2019 protests had on yourself and the wider society?

I think for me right, I realised that the word intersectionality is a tough thing to be practised. What I learned was that to bring this issue forward, you also need people working in different other sectors to come and support, and some of these voices are really missing in climate narratives. Doing the protests, we engaged with human rights groups, we engaged with artists who has given us a space to do our artwork. That Moutou place (in KL), they gave us one whole week for us to buat banner, we did like an Earth or whatever shit. So they gave us the space, they gave us the food. So kind. And I realised from there, there’s an opportunity to engage with people outside the environmental movement. And that’s why I think we can’t just be doing art and sebagainya sahaja, there needs to be a plan how to do things better, more structural, more targeted.

I think the best, I hate to say the word, takeaway is I learned that environmental movement is a lost cause if it’s just going to be run by the environment people. Sorry man, you can’t. It’s just impossible. Some environment people are very tunnel vision, they don’t accept people from [other disciplines]. For example, now I’m doing gender and climate, a lot of people say that it’s not important enough. Professor at UM (Universiti Malaya) told me you’re wasting your resources, your time. Why don’t you go and study, become a PhD [student] than doing this gender research? So I think need to break that mold that only scientists can speak about climate or only people with PhD can speak about climate. Everyone is experiencing this shit, man. How can I not tell my lived reality?

So I think that’s where we move right now for protest. I’m not saying that we’re never going to do that again, we did plan for protest in COP26 and 27 (2021 and 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference). We mobilised students in the UK to come and buat banner ramai-ramai, and then join the climate protest in Glasgow. I totally forgot about that, I kept thinking about Malaysia but yeah, we organised over there as well. So we have students from Edinburgh, from all over UK datang for the protest.

Nadiah at the Forest Plantation Issue Press Conference in June 2020 (Source: KAMY Facebook page)

In your opinion, do you think the work that KAMY as a collective did in 2019 helped to raise the stakes of the floods that would come during the pandemic? Because the discussion around floods were a lot more during the COVID years as opposed to prior to that. Do you think you helped contribute to that?

During COVID, we co-founded a coalition Gabungan Darurat Iklim Malaysia (GDIMY). We were the Founding Members and also Secretariat, and at one point, we were Steering Committee, so we had a lot of leverage to influence people on what kind of narratives we should play. During the floods, we managed to lobby through the coalition. Meaning mostly me lah, I go and ask all the MPs (Members of Parliament) to support. We did a memorandum asking for the inquiry of the floods tahun 2021 to be tabled at the Parliament, to make everything transparent.

Were you successful?

Yeah. So we just called several people only. We called Charles Santiago, Fuziah (Salleh), Maria (Chin), some few people of the opposition. We got into Anwar’s office and he said okay, semua opposition bloc support this memorandum. And then semua ada nama mereka, dia sign. Syed Saddiq pun ada nama dekat situ, so weird. And then he said yes, we will talk about this in the Parliament for this inquiry and true enough, they did talk tapi it didn’t go through lah because they are the opposition. Now they are the government, they should be doing more. But without that coalition, I don’t think we would have the capacity to bring more people into the decision-making table. Like, seriously. The coalition was, I think, one of the most successful things that came out from the protest. That we managed to get people with different ideas, different approaches to sit down and decide let’s create a coalition called Gabungan Darurat Iklim Malaysia. After that, we began to do the white paper. That is also a consultative process with different groups, there were around 35 groups at that time. So I think it all started from the protest. You give visibility, people are keen to contribute, people see oh there’s a momentum, let’s build it. And we survived through COVID so I’m glad. Now GDIMY just finally got funded, so hoping for good things to happen in the next few years.

In where you are right now, do you think protests will still be effective for your organisation and for your cause?

I think we need to do protests. The reason why we’re not doing is because we don’t have enough manpower. We are doing the programmes and the programmes are like, research and these are all really tough skills kan. Not saying that protests are easy also, but you’re doing research, you need to bring objectivity. There’s a different challenge to it, it’s intense. And then we are doing research into something that orang tak tengok, macam Indigenous people, gender, so there’s already a barrier on that.

But we really do hope that we can organise climate protests again, we really need to do so. Not just climate protests, you can do Occupy, you can do a lot of things. We are now more connected to the global movement and we have more tactics to learn. Not the Just Stop Oil lah because I don’t think we can replicate something here in Malaysia, that would just cut off everything. I understand why Just Stop Oil has to do that with their government, but here in Malaysia, I think we have to find our own rentak, we have to be very strategic and we need to do protest.

I’m not saying that just being registered, therefore we’re not doing protest. We want to do it, we just don’t have the manpower. And I think because we are a young group kan, getting registered was also hard. Suddenly you need to do auditing, suddenly you become entrepreneur, you have to do all by yourself, cash flow, things that I never thought I have to do. So it’s a lot of learning on my end. The first few years is tough for us, but then I do hope that the next few years, we can restart again and do this climate protest. And I think we can.

Now that the coalition is really up and ready, we have a lot of passionate people there, we can do that. We just need to find the right time to do it. Too bad that the Asia-Pacific Climate Week (2023) is happening in Johor. If it’s happening in Kuala Lumpur, we’ll do a protest. In Johor it’s a bit different lah, it’s a bit dangerous. We were like, is that why they’re doing it in Johor? So Malaysia is selected as a host for the Asia-Pacific Climate Week, it’s hosted by United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This is a week before COP. So we are planning some few events, but we actually wanted to do protest. Suddenly we know that the venue is in Johor, then it’s a bit tough lah.

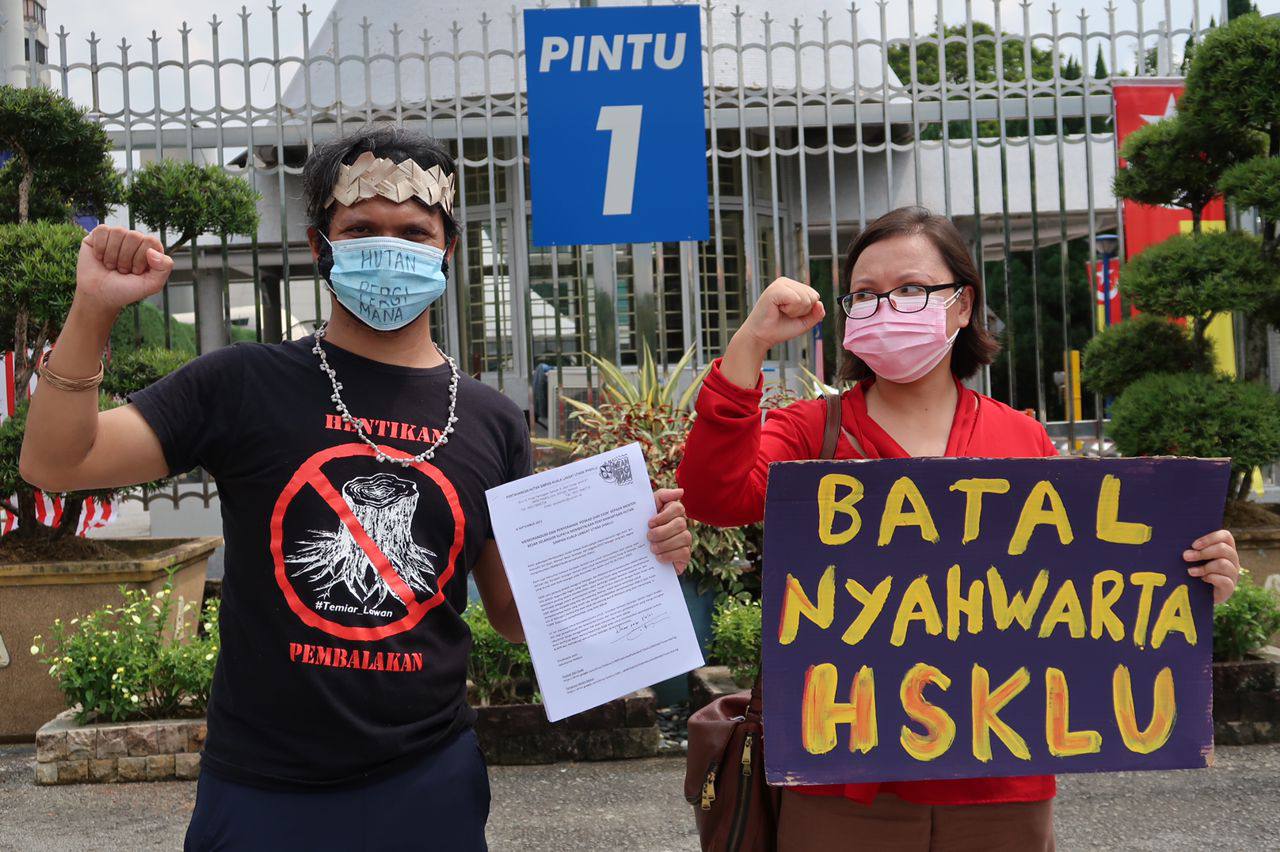

Submission of the Pertahankan Hutan Simpan Kuala Langat Utara (PHSKLU) memorandum to the Menteri Besar of Selangor. (Source: SAYS provided by Nadiah)

When you decided to get registered, was that something you felt like you needed to do? Was it something you thought would help you amplify your voice?

I want to add on to [protests]. Now that we have gathered a lot of data, we are getting a lot of support from grassroots, most likely if you do a protest, a lot people will voice out it’s very different than 2019. I was quite worried because the protest that we did in 2019, we didn’t get a lot of environmental groups to support us so they don’t come in with data and stuff like that. But now we are creating our own data, so we can substantiate our claims, we can protest and talk to media, we will have very clear demands. It can be done.

To come back to your question about registration. From the experience that I had in Germany, people are not registered. No one is registered but there’s a transparency around money, they are organised, even across the refugee migrant movement over there. Tapi Malaysia, I’m scared if we’re not registered, then we would have problems in terms of transparency, we would not get that structure that we need to actually demand accountability. And if we are not accountable, then how can we demand for others to be accountable? So being registered actually gives us the drive to make it a bit structured because this is Malaysia, man. This is not Europe, I understand. The money, for example. We know that we are definitely not going to get funding from Malaysia, we probably get funding from outside Malaysia, so let’s get registered. If you’re not registered, it’s harder to process.

So I think it’s needed to get registered, and that does not diminish in any way that oh, now we are registered, we don’t want to do protest, no. We just don’t have the manpower right now, but we are building the foundation. Now, gender groups have more clear idea of if we go to protests, this is what we are going to say. If we do this, this is what we’re going to do. Before that, there was nothing. So now there’s more people with clearer idea of why they need to come to a protest, why they need to be active in this. Before this in 2019, I would say that a lot of people joined it because they were angry at one particular reason, but climate change is a long (term) thing. Like people were angry about the haze right, but after the haze is done and then you thought eh, mana semua orang? So now we are building. We still need to talk about this (regardless of) no haze, banjir, tak banjir because this is the question of timing, of when it’s going to come. We need to be prepared.

So now we are preparing, preparing, preparing people. I think that building capacity of people is really great to sustain. What we did in 2019 is great because we did a lot protests, we built visibility, and what happens after that is absolutely critical. We co-founded the coalition, we built capacity of coalition, we engaged with people outside environmental groups to build narratives together, grassroots, I think those are equally important. And if we do have a strike, I think it’s not going to be a protest. I hope to have a strike, because strike and rally different kan. The only group that we haven’t managed to engage with are trade unions. Tough.

Now, you’re getting a lot of facetime with the government and have been able to solidify yourself as a serious player in the scene. So how do you think about your protests in relation to your access to the government these days?

Right, there’s that balance that we need to be aware of. I think by doing research and things like that, we actually solidify ourselves as a group. I’m not saying just doing protest is not serious, but then you have data to substantiate tau. To tell people this is actually happening, these are the voices of people that we have collected, so we have the right to stage a protest. Credibility. And then, there are so many times where I had meetings with government and I had to do interventions. At times, they were appreciative and there were times they were annoyed with me, but they can’t silence me, they can’t isolate me. There were some meetings that we weren’t invited and some few other members told us just come Nadiah, and then kita ni masuk saja. Kita masuk terjah and then we stayed. It’s good that we are under the coalition. If KAMY is not invited, the coalition can be invited and then we go under the coalition. We understand some people in the government don’t like us as well, but they need to listen lah. A lot of benda mereka tak nak dengar.

Even COP, they refused to meet with us in Malaysia but when in COP, we met with the Malaysian delegation. We passed the memorandum and the words that they uttered was like kamu tuntut, kamu tuntut, kamu tuntut, kamu ingat kamu siapa? Dia cakap dekat Diana, which is the Orang Asli representative. Dia kata kamu ni semua macam kurang ajar, and then Diana didn’t know how to respond. I was sitting there behind her because I want her to experience speaking to a Malaysian delegation, and then she had a bad experience from there. She said you as a Malaysian delegate to actually be there in COP is such a huge responsibility, that’s one. It’s really tough to go there. You need to get badges, funding, etc. and then once you are there, you need to have a plan of what to do. We were bringing voices from Indigenous communities from Peninsular Malaysia. We go there and meet them, and this is what they say. Ini bukan budaya Malaysia tuntut, tuntut. Patutnya kamu guna perkataan kami memohon, we request. And then when we cerita balik all this to Tijah (Yok Chopil), Presiden Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli,. This is the thing that we need to claim, you have to use kita menuntut. This is not kami memohon, you are claiming your rights. So government people don’t understand that, but we understand where they are coming from. They felt that they are a bit more open if you are being so diplomatic in that sense. But after that, I was still being diplomatic. I said tak apa puan, kami boleh tukar ayat-ayat ni. Tapi asas-asas dia, adakah puan faham? Ada apa-apa soalan tak? I can deal with this kind of people but for Diana at that time, she was so terkejut lah. She never thought that government would respond to her in that way.

So how government responds to us, some are very proactive, some think of us as budak-budak je, some gave us the space but just for PR, sometimes we are seen but not heard, but these are just challenges that we slowly overcome and not to take personally. That is really important, because I know for Diana at that time, she took things very personally. She thinks that these people are supposed to present you in COP, that these are the Malaysian government that will present the interest of Malaysian people, including her. But when she was being told that way, she said that these people should not even be there to represent her. So for vulnerable communities to participate in those spaces, it’s quite tough lah.

Climate March Glasgow COP26, November 2021 (Source: SAYS provided by Nadiah)

In relation to your experience in the protest space, do you think the space is something that is welcoming for women? Did you feel a particular gendered experience having organised and participated in protests? Lastly, what do you think you would do to make the space more welcoming for women?

I think safety. Safety of women is absolutely critical. What I didn’t foresee in Lawan is female intimidation lah. Women and men experienced the protest quite differently. For example, let’s just look at social media. Whenever there’s a picture of Nalina keluar kat situ kan, people would attack her appearance, people would attack her stature, fat-shame her, say oh dia ni India, bising lah, India gemuk macam ni bising. Things like that is there on Twitter, you know. Imagine that.

What else do you think could be done if we want women to take up the protest space more? How do we help prevent a lot of the things you just described in order to get them to feel safe and to take positions of leadership in these movements?

You can’t 100% feel safe, that’s the thing. The only thing that you can prepare is the alternatives. You have to do a risk assessment. I think this is very corporate, but it is the truth for many of the things that are happening on the ground. You want to do protest, you have to do risk assessment, you have to plan for the worst. That’s what we didn’t do with Lawan. Although all these people are so experienced, but I realised we didn’t do any risk assessment. We didn’t have name list of key people who are attending, we didn’t have next of kin, nothing. Now that I’m here in this position today, I think that banyak benda safety kita tak buat. Risk assessment is absolutely critical, and it’s not only towards you, but to the people around you as well. So these are assessments that we have to actually go through first before we can decide is this even doable and things like that.

But there are situations lah macam contoh, kalau Orang Asli kan. Orang Asli lagi lah. In one of the stories we collect for documentation ; They want to do protest, always the male yang keluar, perempuan akan duduk memasak, prepare. The norms are a bit different, but things are changing lah now with people like Diana coming in, having the Apa Kata Wanita Orang Asli. They are more vocal, they want to do more, they want to participate more, and I feel them doing risk assessment tu tak perlu lah sangat susah because they are talking in a situation where they are the affected community. Risk assessment has to happen, but what I want to say is it’s very different and disproportionate. The context for risk assessment to me is a bit different from [Diana], her risks are very high. For example, JAKOA (Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli) would come in and suddenly say kita orang tarik korang punya scholarship, korang semua tak boleh habis universiti. So many different ways.

But risk assessment has to happen lah. I think this is one of the tools that we want to talk about in creating more women leadership to join in protest. But as a whole, you really need to have more leadership of women in not just protest, but in the advocacy space. We don’t have a lot of feminists talking about climate justice in Malaysia and this is something that we are slowly trying to build. The feminist lens to things like climate is absolutely critical because you move away from that urban, elitists, whatever shit, and then this is a way to bring more women into advocacy. Because there’s a lot of really talented, really passionate young women outside urban space that really does good work, but it’s just they don’t have the space. No one is giving their space. For example, this recent youth climate summit that happened during the weekend. To be a delegate, terang-terang tulis kat situ you must be fluent in English. And then all of our teammates are like, then we cannot go lah? We cannot bring Orang Asli? If you said that language is not a barrier, you provide translator. This is how to get more leadership from women outside urban areas. You need to provide quality translation, quality interpreters, financial support for them coming in.

I remember during our protest, we give money for them to come down tau. Like dia tak perlu turun sendiri-sendiri, kita provide. The same goes with all of our consultation work, we provide per diems and things like that. I think a lot of these urban groups that do work nowadays, they just panggil Orang Asli datang lepas tu tak provide apa-apa pun. Expect dia boleh datang, tunjuk, ambik gambar and that’s it. How is that leadership if you’re not being heard? So you need to provide all these essentials for rural women or B40 community to participate in leadership, all these tools have to be there. Kalau tidak, macam mana mereka nak masuk dan bercakap pasal isu ni? It’s really tough for them keluar dari kampung, kena tinggalkan tanah, they are on daily punya subsistence, makan kais pagi whatever. You provide the space tapi you tak provide the means of how people come to this space and participate, then that’s not meaningful participation. Even leadership can’t grow out from there. And the same goes with protest.