Tan Jo Hann has over four decades of experiences in community organising and grassroots advocacy and has trained and mentored thousands of community organiser-facilitators across Asia. He is the founder of the Southeast Asia Popular Communications Programme (SEAPCP) (1991), established Malaysian Human rights NGO Pusat Komas in 1993, was the President of PERMAS (Persatuan Masyarakat Selangor & Wilayah Persekutuan), – a network of urban poor squatter and slum communities (2000-2015) – and served as a local councillor (Ahli Majlis) in MPSJ in Selangor State (2008-2012). He is currently a director of Pusat KOMAS.

Tell us a bit about yourself.

I’m an Ipoh boy, born in Ipoh, a small Chinese mining town. I was born in 1962, so you can imagine lah those days. I grew up like any normal ordinary kid. I didn’t really get conscious or aware of my surroundings or social injustice so to speak, until I came to KL. At that time, everybody comes to KL, as for me I studied in TAR College. Honestly, I didn’t really know what I was doing here, I was not really interested in what I was studying, and why I was studying it. So obviously I was not really motivated, but I saw some things in KL that really affected me. Maybe it was because it was the first time I lived away from home, out of my hometown. This was actually my turning point moment. I saw some kids working in some hawker stores and I remembered very distinctly a small Indian girl, maybe six or seven years old, helping to carry and wash the plates of some fried noodle shop. I saw her “curi-curi makan” (stealthily eating) the leftovers. That really hit me, like what is going on? All my life in Ipoh, everything was quite comfortable, and you don’t tend to think about such things. I just felt very disturbed to see the young girl who had to feed herself in such a manner.

I had many questions like why does this happen, how is it that she can be so poor that she cannot have food? And why is she working? There were too many things and it seemed like I could not do anything. I spoke to all my friends about it and everybody said “yeah, that’s how life is, you know?” But I was not satisfied so I kept on questioning and it actually affected my studies too, because I was not really concentrating. And then, my friends and I tried to do something. It seemed quite silly lah at the time. We just wanted to help the kids so okay just tuition them. But it was quite silly, they were working in the hawker stalls, how can they concentrate when we were teaching them. Of course after some time, they didn’t really follow the sessions anymore and we also could not keep up. That was because we just addressed the social issue without analysis, without understanding deeply, so if we just simply “hantam” (bulldoze through), it won’t last.

After my studies I went back to Ipoh but the incident stilled lingered in my mind, I know I had to do something but I didn’t know what to do. To cut a long story short, somehow I got involved with a Chirstian student organization called the Student Christian Movement (SCM). The SCM was actually quite a radical and progressive student movement in those days, and it had chapters all over the world under the global organization called the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF). In Latin America, they were part of political changes and revolution and stuff. In Malaysia we were very controlled but somehow I was lucky to get involved and we talked about social injustice and so forth.

Is it considered the norm for Christian organisations to discuss such things?

It was not normal at all. It was fortunate for me to meet a few senior members of the Student Christian Movement who were very active in student activism before. Through our discussions things started to make sense to me, I realized then that what I saw, the poor girl who “curi makan” and all that was one of the examples of unjust social structures and injustice. And we used to have study groups and we read about what happened in Sri Lanka and India and other social situations. I remember we struggled to read a very long (10 pages) and wordy paper about the world order, it was very complicated and the analysis was very hard for us to read. We also read Marx, Engles, Das Kapital and other works but in everything we read, half of it we didn’t understand. The point is we got exposed to it and for three years in Ipoh, I was with this group and finally we thought, okay, we cannot be studying forever lah. Let’s do something about it. How do we put our commitment to practise?

Where would all of you meet?

Ironically, in the church. I mean, this is not usual. The churches in Malaysia are very conservative. It’s only of late that they have become more and more socially concerned, for instance even supporting and joined the BERSIH protests. The Catholic Church for instance has a rather strict tradition but they also have a very strong tradition of social concern which is a good thing. Many social activists actually have a strong Christian background.

They are exposed to liberation theology?

Yes, many of us were exposed to and were influenced by liberation theology. I come from a Methodist background, it was very strict, and very methodical. Although John Wesley was the founder of Methodism, he also organised the people and had many social concerns. But you know lah, when things become institutionalised like the church, they’re only concerned about building a big building and all that. That’s probably what drove me to start my own activism by becoming a part of the youth movement in the church in Ipoh.

When was it?

When I returned from KL in 1981, 1982, I was then the chairperson of the youth organisation in the Methodist Church. We were able to organise a lot of youth in the church and shared with them social issues, analysis, based on the teachings of the Christian faith and so forth. We were then like a “rebel force.” A lot of adult church members were very conservative and can be really oppressive. They call themselves Christians but they actually exploited church workers, so we stood with the workers. For instance, they had sacked a kindergarten teacher who dared to stand up against these senior members and we stood with her. We fought for her case and because of that they closed the youth organization and kicked me out of the church leadership. We created quite a ruckus in the church to the extent that the President of the Methodist Church from KL even went down to Ipoh to intervene.

So we retaliated by organizing the youth not to go to church one Sunday. We felt so brave lah, and when the youth didn’t go to church, it was half empty. The adults started wondering what happened to all the youth? Why didn’t they come to church? So we put up our statement on the church notice board, and said that the death of the youth organisation was in the hands of those senior church members. That was really a protest movement. I suppose the seniors felt we were getting too bold, and in every church committee meeting we always fought and debated, and since were only 18, 19 year old teens who were we to question these senior 50-60 year old church leaders.

Jo Hann & PERMAS members in solidarity with the National Union of Bank Employees (NUBE) protest against bank management in 2012.

That’s a very interesting background because in 1987 then, Ops Lalang happened and most of the people detained had connections with the church.

Yes, a few of us strategically joined a seminary in KL because we wanted to “infiltrate” the church. We thought that since the church was not doing its job, we have to go in, become pastors and organized different churches and their respective congregations. We were quite idealistic 19-year-olds then. For me then studying in the seminary was quite a horrible experience, it was very bureaucratic and very controlled. It was killing my spirit so after six months, I quit. That was in 1982, 1983 which was when I started getting involved in organizing the urban poor. In those days we didn’t have many NGOs and especially openly operating, thanks to Mahathir Mohamad (Malaysian Prime Minister then). He instilled a very strong culture of fear amongst Malaysian and so when you say you are from an NGO, they will immediately brand you a “syaitan” (devil), and get funding from the US and act as their stooge. Or that you are part of the opposition political party or you are a communist. Those days were like that.

Around 1983, a group of us organised communities. At that time, the KTM (Malaysian Railways) were building the second track in Semenanjung (Peninsula) Malaysia all the way from the north to the south. The government had decided to forcefully evict 300,000 people along the railway tracks, so my group and I were organising these people in the KL and Selangor area, (including) Segambut, Kepong, Port Klang, Sentul. So every night, we would be walking along the railway tracks to the communities because that’s the only access. Suddenly a train will come, the bright lights shone into our eyes, the loud honk blasting our ears. Those days, like that lah. Then we organised the communities, taught them how to write letters, protest and so forth. So in the 3 years before I went to Philippines, I was very heavily immersed in community organising, grassroot organising. So we went all over KL and Selangor every night.

We also organised plantation workers, rubber estates such as Kerling, Tanjung Malim, Kuala Kubu Baru, and others. I was the youngest among our group. There were 13 of us, all walks of life. We had students, teachers, even journalists. And people like us who have no regular job, so we follow everywhere lah. I was the designated driver and every night, I would drive 200 km in a small van and we go around to all these places meet the communities and discuss their issues, plan for actions, those were really vibrant days. Sometimes when we go to the rubber estate in Tanjung Malim or Kerling, suddenly the military intelligence would be waiting for us. The community leaders would warn us not to enter the estate. Those days we didn’t have handphone so we would drive there and the estate leaders would intercept to warn us. And we would literally run away lah. Then we would drive to the next town where they would meet us in a coffee shop or friendly house. It was all really like really cloak and dagger.

Those days were like that, you don’t have that freedom to move. We don’t go around with the name (of the) organisation, for instance Pusat KOMAS, no way. You’re just a group operating quietly and then you hide under different covers. One of the covers we hid under was a consumers’ movement, more safe kind of thing. Luckily that person who was in charge of the consumers’ movement was also sympathetic and allowed us to use the name. SBs (Police special branch agents) would look for her to ask her if some of her staff members had gone to a certain community and she would just cover for us lah.

Fast forward, in ‘86, I left for the Philippines. It was like my assignment to go to the Philippines to see what was and to learn whatever I from there, come back and continue to organise our communities. Also to not commit the same mistakes in organizing committed by our Filipino comrades. That was my mission. So I went there and studied, but most of the time I was with the solidarity movement in Philippines, supporting campaigns and all that.

Those campaigns were primarily around urban poor?

Not only urban poor, but everything. Solidarity movements like Gwangju Massacre, East Timor human rights violations. Then when 1987 Ops Lalang happened in Singapore and then Malaysia, of course I wanted to go back but I was advised by my group to stay away since they were also in hiding. They said “you better hide in Philippines, so for two years I didn’t return from the Philippines, but I and others friends mounted protest actions in front of the Malaysian embassy.

But then among the Malaysian students there, there were some spies and somehow they knew about my actions and my identity. An embassy officer called me at 12 midnight one night and she told me she knew what I was doing and dared me to show myself at the Malaysian embassy in manila. I politely declined and stayed away from Malaysia for the next 2 years.

At that time, were you on scholarship?

No, I didn’t have a scholarship. I went on my own with my sister and my family’s help. I also worked there doing editing, writing and layout jobs. The cost of living in the Philippines was quite cheap then. I had a lot of friends there and we participated in many protest actions such as the Mendiola Massacre, where 14 farmers were shot down by the armed forces for marching to Malacañang palace. That was one of the first embarrassing moments for the new President Cory Aquino. She was supposed to be a reformist but there were also many internal military struggles. I was also a freelance photojournalist then so I shot lots of photographs and stuff like that. I think the entire 7 years Philippine experience was very helpful and really gave me a lot of perspective as I saw a lot of things and it helped me decide what I should and should not do.

When things had cooled down after a few years, I came back and talked to my group about what we could do and everyone told me that things were very, very tight now, and everybody was afraid and careful especially in criticizing the government. But we continued with our organizing. There was a general election after Lalang. The opposition was coming out quite strongly because their people also were arrested, Lim Guan Eng and all. It was the first time our group was involved in an election campaign. Sometimes politics split people and it had happened that time. Our members were divided in supporting different candidates and this became the splitting point in the history of our group with some members divided into 2 factions. One side wanted to be involved in the political campaigning while the side held strongly that we should not be involved in partisan politics. Nowadays, of course we openly talk about NGOs and politics. But before that, it was very difficult, if you’re with the NGOs then you are NGO. If you’re seen to be with politics, there are risks of being identified with opposition parties seen as taboo by the government. Although it was our political rights but to be identified with the opposition party then, you will be targeted by the government. Although my group had split into 2 sides, we had continued organizing communities in our respective areas.

I came back to Malaysia in 1993 and resumed my organising work with the urban poor with some of my former comrades. We had established PERMAS (Persatuan Masyarakat Selangor & Wilayah Persekutuan), a registered society with the registrar of Societies. PERMAS was very unique as we were a society and could legally form local committees in different communities, this was our power to officially and legally entered communities and organized them.

How did you get access to register your society as such?

We were quite lucky and with the help of a friend we wrote our own constitution and by-laws and got ourself registered as a society. We were careful not to put words like politics, human rights etc, but instead we mentioned words like business, small enterprise, community activities and so forth. This was very helpful because in our community organizing work we had to deal with government ministries which always asks us to state our legal status. This way when we are challenged by the government officers, we would assert our legal identity and that would shut their mouths. For instance, when we were fighting for adequate housing against DBKL (Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur or KL city hall) their officers would always try to exclude us when they meet the community. With the legal identity we could gain access into these meetings which were very important to ensure the people were not bullied by the DBKL officers.

At that time, did you face any risk of your organisation being banned?

Yes of course we did, but we didn’t consider that. Number one, we were not talking about politics and overthrowing government, we were talking about housing. There is nothing wrong with talking about housing for the poor. For instance, when we organized a protest action at the Hulu Langat District Office because the community had no water supply for several weeks, the community of 20 people with children and old folks were met with heavily armed police personnel holding rifles and other weapons. Water issue. Only 20–30 of us with children. Oh my god, they called the police, came with machine gun.

You said you organised people along the railway lines, so we just want to hear a bit about your first time going for something like this. Did you feel fear, how were the people, when was it roughly?

The first time I followed my seniors into one of these railway line squatter communities it was in 1983, all I knew was to follow the lead from the seniors. Although we had been exposed to these communities before when we were students on an exposure trip, but working directly with a community is another thing, so we cannot be “cocksure”. My role then was to be in charge of the mahjong paper, marker pens, masking tape and to put it up when needed. And to sit there and listen and learn. Most of our communities then were Indian communities, so the Tamil speakers among us conducted the meetings and those who could not speak Tamil were lost for almost 2 hours, so when they instructed me to put up paper, I would just stick the paper and then sit down again. Those were the days and this helped us gain important valuable experiences. But you need to be committed. If not, you would just give up. For some of us we had chosen to do this, so we really worked hard. Hard in the sense that after some time, I can actually understand the gist of the discussions in Tamil and some of us even took Tamil classes for 6 months to a year. That was how committed we were. I could actually read Tamil and until today I can still remember some characters in the newspaper but I cannot understand everything lah.

PERMAS & the Kg. Railway (Sentul) urban poor protesting for their housing rights in DBKL (2009).

In those days, just to give you an idea why we were only working with Indian communities, because the possibility of working with Indian communities were higher. You had no chance to go into Malay communities, no way. And there were not many Malay activists then, so when you go into a Malay community without a Malay organizer in your team, you are asking for trouble. Who will listen to you? Even if you have a Malay activist with you but because you are not representing a political party, not from the government, oh, you must be a communist! That was how the communities perceived and portrayed us. This actually happened to me when we were organizing the squatters behind the Batu Caves temple, it was then a mixed community of about 3,000 people called Kg Laksamana. There were a lot of intense activities there with gangsters and MIC involved. Those years were very difficult to move about because Malay communities controlled by UMNO, Chinese communities by MCA (Malaysian Chinese Association) and Indian communities by MIC. Their local branches control these areas and many of them are gangsters and some are engaged in shady business. They would work with the construction companies, the “pemaju” (construction company) to get rid of the people for money. We saw this happen a lot especially in Kg Chubadak Tambahan in Sentul where allegedly a letter with UMNO letterhead which mentioned clearing the area soon because the construction was needed to be done. There was a very strong presence of political parties, especially government political parties in every community.

Our strategy each time we enter a community was to form an alternative committee and leadership, and that usually gets us in trouble because we will be threatened by the present leadership of gangsters and so forth. To protect ourselves, we also influence and recruit “gangsters” into our committees. Otherwise we cannot survive. For instance in Jinjang Utara longhouse, the biggest rumah Panjang settlement in the control, with 4 areas (A, B, C, D) with about 8,000 people, there was gangsterism, drug dealing and addiction and alcoholism. The police used to raid the place all the time. So with the protection of our own “gangsters” we could operate, these guys they had jobs like debt collector, bouncers, bodyguard drivers and so forth. You just got to work with that and in the process we try to change them as well, it’s not easy. But that was our task and that was how we operated.

As a first timer entering the community we really needed to learn a lot and then after a year or so, we learned the ropes so to speak. As for me I was then in charge of organizing about 3 to 4 communities in Port Klang, and in Sentul. After a year or so of organising urban poor communities, I was also tasked with training new “recruits” when I myself was only “half-baked”. So I used to tell them just follow me into the community, and asked them to put up paper when I told them to do so, the same way I had learned before. Our experiences were mainly on the ground and we learnt to deal with all kinds of things. It was really a lot of work, but we were young then and we were full of passion and energy to work with the people. But in those days, we didn’t have a systematic way to learn. Nowadays, you have all kinds of training and capacity building. Firstly, we didn’t have money, secondly you could not organize trainings because it was quite dangerous the police will shut you done. You could not do something like that in a hotel or something so we hid in somebody’s house and brought in the people quietly and conducted our training in the house. And if the neighbours saw and reported to the police, we mati lah.. We had very tight conditions and we learned from those experiences.

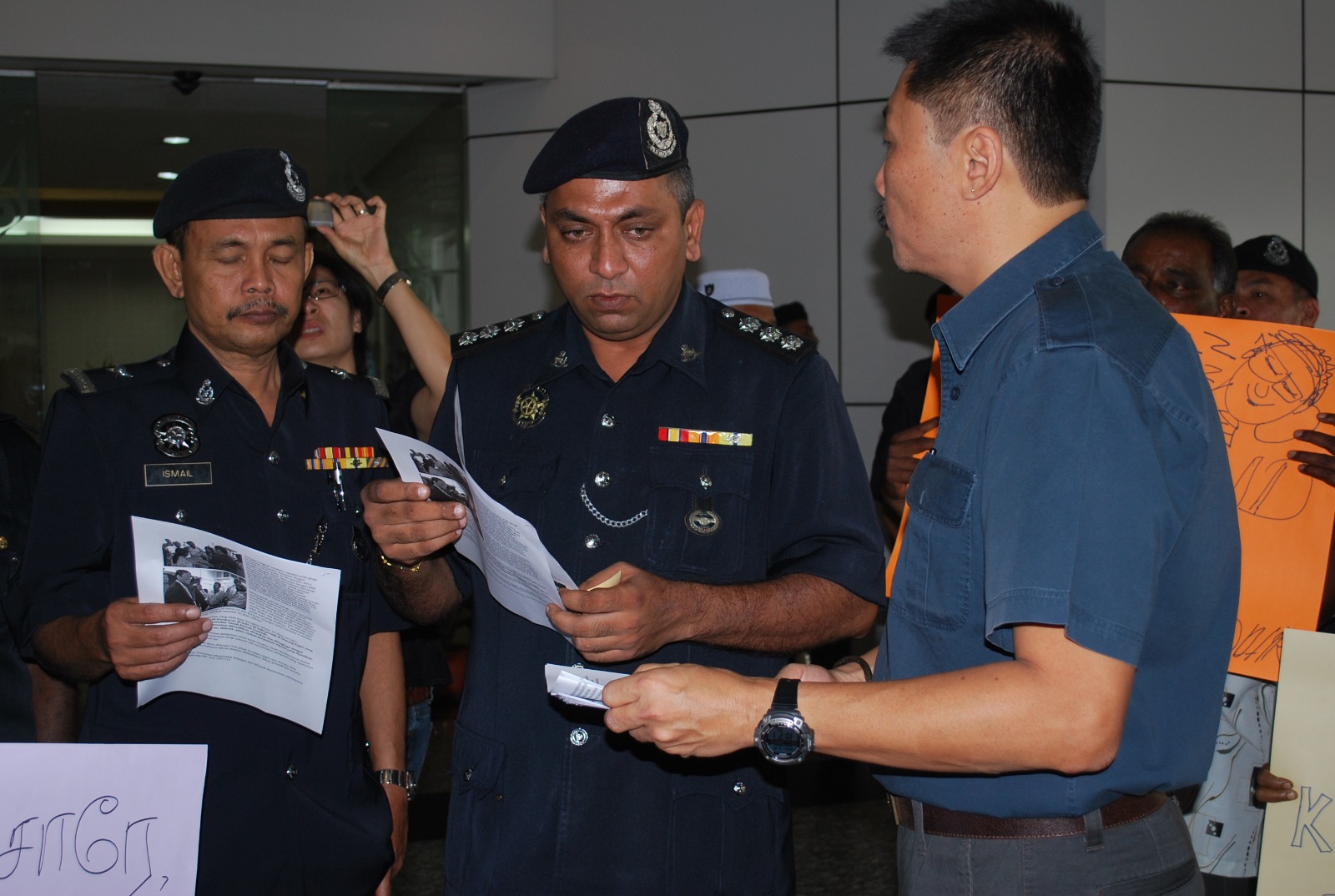

Jo Hann negotiating with police officers during the protest in SUK Selangor where PERMAS and Rawang rumah panjang residents demand their promised land (2010).

Was it the same in 2007, 2008 and all the way up?

I would say being in the NGO movement for over 20 years then, at one point I really felt like giving up. Really things were so hard especially after Lalang and especially when Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad was in power. Everything was so tight and strict that you just can’t move. After some time, we reflected what are we doing here? We are not moving forward, everything we do is controlled. Then Reformasi happened around 1998-99 and that actually helped a lot because Anwar Ibrahim came out from the government and so we NGO people saw an opportunity since the government seems to be fighting among themselves. Anwar came out and teamed up with many ex-UMNO guys. It was interesting because they used to tell us the kind of dirty tricks thay had used when they were in UMNO, for instance how they would tell the old grandma that if she did not “pangkah” (cross mark) the “dacing” (image of the scale, the BN logo) her electricity would be cut. When Reformasi happen, it gave us an opportunity to enter Malay communities. I remember going into Malay urban poor communities with many haji-haji members wearing the kopiah.

Where exactly was the Malay community?

For instance, Kg Chubadak in Sentul, Balakong, Wira Damai, many of these are unknown small Malay kampungs in KL and Selangor. We were also being referred to from one community to another as advocates for housing rights and we were also featured in the newspapers a lot, especially Chinese newspapers, I suppose because the PERMAS President (me) is a Chinese. We received a lot of coverage from Nanyang Siang Pau, Sin Chew, China Press, and others. And also because we talked about housing for the poor and not politics directly the newspapers were not afraid to cover us. That was how we operated in those days, PERMAS was (getting) more and more significant in that sense. We cannot imagine a Chinese face like me going into a Malay kampung alone and meeting in the surau. When it was time for prayers, I would excuse myself from the surau so they could use it for prayers. It was the first time we had that kind of cordial relationship because it was based on common interest. Now I know they needed our help to fight for housing and they were very desperate so they come to us and we did not have to look for these communities. For instance, the longhouse Malay community in Balakong is already a middle-class housing and commercial area now. When we worked there our local leaders were all former soldiers so they “tak takut mati” (not afraid to die) kind of spirit, and this helped in our organizing work. They said “we have been into the jungle and war situations, but what do we get in return, we have temporary housing.” In those days, things were not very clear. Sometimes Malay communities who asked our help had usually already approached UMNO before that and were either refused or played out, so they resort to NGOs so then come to PERMAS. The problem is they usually came to us at the last minute They would say “Yeah, bang, sorry lah bang…” (Yes brother, so sorry brother..) So we would say “Ok it’s alright, we will try to work together but don’t blame us if you get evicted because you came to us so late because you went to UMNO first…”.

Kg. Kerinchi in Bangsar South was also another similar example, we had been organizing the area for more than a year then when the newly elected member of parliament for Lembah Pantai called us to help her deal with urban poor communities in Kg Kerinchi. One thing is community people are not all innocent, they are mainly survivors and some of them would sell you out if they can gain something from it. This community had already settled the deal with the pemaju (contractor) and had already gone to the housing tribunal which awarded them a certain amount of money each. They had already taken the money but after that, they had second thoughts and realized the amount was too little for them to get another low and medium cost apartment unit. Fourteen families had stayed and refused to move and one week before the date of eviction, they came to us and we checked out all the dasta and information and already knew the complete story behind their issue. We stood with them nevertheless and on that day when the bulldozers came, we held our ground with them including the MP. UMNO guys surrounded the place and started throwing stones and harassed our people. Lucky on that day the police was quite fair and actually protected us and did their duty properly. They even arrested the stone throwers. If the Police had sided with the UMNO guys we would have been injured badly that day.

That was Reformasi, so that started the crossing of the line between NGOs and politics more and more. During general elections NGOs would align themselves with different parties in campaigning and supporting different parties and candidates. But in 2004, when Pak Lah (Abdullah Badawi) became the Prime Minister things had remained tight despite Reformasi.

NGOs protest near parliament for freedom of assembly and expression.

During the 2008 General elections NGOS again went all out in supporting and helping different parties in their campaign, and many also conducted voter registration and education. Many NGOs mobilized people to support opposition parties especially those with a reformasi agenda. I was the campaign director for Klang MP Charles Santiago, who was an NGO person with a strong social and background and agenda. In Klang, we dealt with lots of gangsters, it was very crazy. A lady who ran the hardware shop, and I guess she must have been a Pakatan Harapan (PH) supporter told us some people came by her shop and had wanted to buy all the small axes from her stall, and she had recognized them as BN supporters. At the end of the polling day when our counting agents were trying to leave the centers, BN supporters had surrounded the area with several cars, our agents told us they were afraid for their lives and stayed inside the center until we sent a few cars with our guys to the center to escort the agents out of the center. But anyway the point is, the relationship between NGOs and politics become stronger and clearer as we were now openly involved openly unlike in the 1980’s and 1990’s. In the March 8 2008 general elections In 2008 the opposition party, PH themselves didn’t really expect to win so many states then, they were really surprised when the votes were counted in each constituency.

How did you perceive that situation? Because you are coming from the grassroots, did you actually see that coming?

No, we didn’t see that coming. We just thought maybe we would just gain more votes or possible more seats, but not winning over entire states. We were quite shocked. I remember the way we campaigned, we were so poor then and in Klang, we didn’t have a proper campaign base but used an old bungalow house with a big front yard which we used for nightly ceramahs (political rallies). We felt proud because hundreds of people will come and listen. I had to do everything, eventhough I had a team of almost 20 people formed into 12 sub committees. I am the Campaign Director and when it rained, I had to literally and physically clear the water from the garden in preparation for that night’s ceramah.

The day after polling day, some of us NGO leaders and friends such as Jerald Joseph, and some from Suaram and Pusat Komas had gathered to reflect about the outcome of the electionsand we already sensed that this was a big leap forward for our NGO movement as well. So we initiated a gathering of NGOs and civil society organisations (CSO) to discuss crucial developments and possible steps of action to seize the moment so that we are not left behind or worse miss the boat totally. And we felt that we had to do this before the newly minted governments in Selangor, Penang, Perak, Terengganu, Kelantan, already plotted their agenda and not consider the vital role of NGOs and CSOs in this new development in Malaysian politics and society. We had to be quick and clear in our negotiations with these new governments. In the CSO meeting there are almost 100 different types of NGOs, and we hammered out our demands and “wishlist” to the new governments.

Where exactly did the meeting happen?

We had the meeting in the Chinese Assembly Hall, with the NGOs ranging from progressive ones to welfare and even service oriented NGOs. But it was good that they came which meant these groups also realised that had been political changes and they wanted to be a part of it. That was when we formed a multisectoral NGO alliance to deal with the newly elected governments. We organised ourselves and formed 14 small committees. For example, the urban poor committee was headed by me with different groups in its membership such as PERMAS together with JERIT (Jaringan Rakyat Tertindas), and others. The main objective was to engage with the various state governments and push for our agenda. Unfortunately not all the committees were very active, but the indigenous people committee where Pusat Komas was part of had worked very closely with the Orang Asli, JKOASM (Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli Semenanjung Malaysia), with leader Tijah Yok Chopil and their team.

The sub committee I headed with the urban poor groups was strong and active. Fortunately, the exco member in charge of housing in Selangor then was Iskandar Abdul Samad. I had known him from way before when he was not an elected representative then, but was just a PAS member who supported our issues in Ampang where he was based. He used to follow us during the protest actions in Pandan Indah, Kampung Berembang and other areas in Ampang Jaya. This made our engagement with him easier as we already knew each other. As the new government, most of them were also learning by doing as they went along, so it was a good time for NGOs and CSOs to push forward, and we did. We had formed a special committee under the Selangor State Exco member (Iskandar) which was convened by me officially appointed by the Iskandar.

Many NGOs including myself then did not really have a good grasp and knowledge about government structures, roles and separation of powers between the federal, state and municipal government. After 2008, all of us had to learn about government and in Pusat KOMAS we started to focus on this subject calling it “citizenship education”. I was selected to serve as a local councilor in Subang Jaya (MPSJ) and that made it more urgent for us newly minted councilors to learn about the government. Pusat Komas did a lot of research and we churned out materials, videos for educational materials and we spread it out. We also reached out to the new government, offering them these materials for them to educate their own members and even officers in the new governments. Now this is where again, sometimes were very frustrated because when we offer support like that, we didn’t even charge them a cent. We just produced the videos and offered it to the Mentri Besar (Chief Minister) then who seemed was keen and actually ordered 50,000 copies of the CD. We made the 50,000 copies and they later told us they didn’t want it anymore because of budget constraints. We were left with the CDS which we already made and on top of that we had to pay from our own pockets to cover the costs of producing the 50,000 copies of CD which amounted to about RM70,000–80,000. Things like that happened but anyway, because we were involved, we were in the local government, we were part of the government, we were engaging with the government, so we just quietly accepted all that.

I had work very closely with exco member Iskandar. Whenever he had issues in the urban poor areas, he would call me to go with him. And then meanwhile for our own work in PERMAS that was quite a good boost because we had the Selangor government Exco supporting our issues. But still, we had to deal with DBKL (KL city Hall) because it was under the Federal government which was then still under the BN government. We still had to deal with problems like Kg. Kerinchi, Jinjang Utara and all that since there were within KL boundaries. For instance, Jinjang Utara longhouse is the biggest and oldest in KL with 4 areas, 8,000 people and we had been with them since their set up in 1993 which was about 30 over years then. So when we work with an area, we cannot just simply come and go but to continue with them, including seeing their children grow up from being a baby to an and now even getting married and having their own children.

Squatters from Old Klang Road protest their eviction in DBKL (2008).

How do you utilise resources to mobilise and give exposure to these issues to the public?

We conducted a lot of trainings for different community leaders, from Indigenous people to urban poor areas to students, as many as we could. We worked closely with Pusat KOMAS which was founded by me to support grassroots communities in capacity building and creating popular communications media tools for human rights work. PERMAS had the mass base with about 14 over communities from all over covering a constituency of almost 100,000 people. I mean including families and all that. And then KOMAS has different capacity building programmes, and tools so it was a good match. The materials and videos produced by Komas would be used for the mass base and usually in the form of cartoon, comics, photos, and visuals for simple and more effective reach. We made the booklets in five languages including languages in Sabah, Sarawak covering different topics touching on knowing about the government at different levels, your rights, and so forth. For instance, Pusat Komas did an educational video called “Ahli Majlis Penghubung Masyarakat” (Local Councilor-the community facilitator), which featured the work of four councilors including myself through first hand experiences. These materials were very helpful for people to learn about how to deal with the local government, for instance when you have a garbage problem, who do you go to; which department handles housing issues and so forth. Four years as a councilor had taught me a lot, gave me a good perspective on governance, and I now know it was not easy to be in the government.

Earlier, you told us about asking one ‘kakak’ (sister-referring to a woman) to go do police report. Can you tell us more about this? Was she actually exposed to this kind of knowledge?

The community organising principles are like this, that we always empower the people to be able to do things on their own. From the very start, whenever and wherever possible, we will always do that. Number one to empower the people. Number two is to involve and empower the women. In most communities it is always the women who are always behind the men who usually take leadership roles. It is not about being politically correct, but because it just makes sense to have women as part of the leadership and decision making. For instance in Puchong, I remember an urban poor community which did not involve the women, and because of that the women were tricked by the contractor into signing a document stating that they are willing to move out of their houses. The pemaju (developer) would usually wait until the men goes to work in the morning, and then they will come to their houses and speak with the women and usually telling them stories to scare them or make them sign something. So we tell the community that they have to make sure the women are also involved in the meetings so that they will know what is going on and not get cheated. In some Malay communities especially, most of the women would hide in the kitchen and peek into the room where the meeting is ongoing, and I would always find a way to get them to come out of the kitchen and join the meeting.

In community organizing we empower the people with skills, knowledge and information so that they become more confident. Skills in dealing with the police, government officials and so forth. Can you imagine when they come into a minister’s office, especially Ministry of Housing and Local Government, they are already nervous and feeling so small. The first thing when they are confronted by the security guard they already feel so lost, and from that point onwards they would have to fight all the way into the government offices, if they are lucky. So we teach them tricks and tactics on how to deal with all these bureaucratic processes. A lot of them are not good in writing but I still ask them to bring books, newspapers, and writing materials. This way when we meet the government officials our side would look like we have a lot of information, done our research and will diligently record every word they say. I would tell them to pretend to write and record the meeting so that the government officials will not simply speak nonsense. The government usually bullies the people like this but if we learn how to deal with them, we can actually level the playing field and give the people a fighting chance in advocating their issues. The government people always use mind tricks and psychology to scare the people but we also have our own tricks to push back.

Sometimes, the people must learn from their mistakes. For instance when they go to the police station or meet the government, some government officials would use racial politics to divide the people. For instance when we were organizing the Malay community Kg. Chubadak Tambahan in Sentul, we had a very strong local woman organizer Kak Wan. She would confront the police without fear and even fought with the FRU forces, when they came to the Kg to support the pemaju in evicting the people. So in one of these meetings with the government officials in the DBKL, I was the only Chinese face among a sea of Malay community people. The officials would always point out and question my identity and if I was part of the community. The people would explain that I was the PERMAS President and they were all my members. They would use racial slurs like “I don’t care if you are the Chinese association but you cannot join this meeting…” The people would then firmly say that if I was not allowed to go in they would all not go into the room. They are usually quite taken aback and surprised why a Pak Haji community guy would defend a Chinese man like me..in their minds, Malays should stick to Malays, meaning they should be listening more to the Malay government officials than to a Chinese guy. Sometimes the official would just go along with this but some would just declare they would not say anything in the meeting if they insist on me joining the meeting. This is the kind of racial crap they do to divide the people. Sometimes I would say “Ok if you do not want to speak it is ok but make sure you listen to all the things we have to say to you.

We actually deal with a lot of situations, some turn out positively and some others not so. Sometimes there are good government officers who would help us and unofficially they would tell us stuff outside the meeting. For instance the PPR (Program Perumahan Rakyat) low cost housing project by the government, we used to urge the government to implement the “sewa beli” (rent to buy) scheme but the government had always rejected our suggestions. But at one point a deputy Director of housing told me outside the meeting that he had actually brought our suggestions to the Minister and they were quite interested in the idea of sewa-beli. Then one or two years later, it was announced in the newspaper that. Not to claim credit, but we were already happy that this was finally being done and we can at least say that our way of advocacy had yielded some results, even though it has never been openly acknowledged. The government wanted their ‘face’ kan, so we let them think it is their idea. These are the tactics and strategies and if you don’t have that experience, you cannot know this.

This kind of ground experience is very important because when we deal with the people and talk about movement, this is the movement building. Every bit of this such as how to deal with the police, government and even pemaju including different positioning, posturing, and applying different strategies. If you want to build a movement, attitudes, skills, values, relationships, respect for women, all of them matter as part of the big picture.

Bersih 3.0 in 2012.

At the end, sometimes only protest works. How do you actually convince people to go out and protest?

I would put it in another way. Actually, it’s not about whether protest works or not, it’s about how you use protest and when to use it. It’s a weapon, it’s a tool, you have to use it very wisely. I know people seem to think that yeah, we shout and shout, nobody listens. So we protest, and then they would listen. Not necessarily. Look at BERSIH. We went out to the streets two times in masses. After that, what happened? In that sense, our high profile big protests received much attention in the whole world but what did we achieve? I’m not belittling it, because I was also a part of it. It means that it’s not only protest actions. Protest is a very powerful tool and it’s good to shout at somebody hey, listen to me. But when they respond “what do you want?”, we need to able to engage with follow up and concrete plans otherwise, we are shouting for nothing. The protest is for nothing if you don’t follow-up with working closely with the people and organizing the communities.

We held many protests in those days, at the Ministry, in the District Office, in the Municipal Council, usually in advocating housing for the poor issues. But in between protest actions what did we do? Before and after the protest, there are lots of work to be done. After the protest, the lobbying, the writing of letters, the press release, the meeting, making appointments to meet so and so, because since the protest had been carried out so what else would you do? Ironically even under PH government we also had to do this. For instance PERMAS had a long land struggle issue involving the Rawang longhouse community which was evicted from the railway tracks some years before that. PERMAS had been organizing that community for 33 years and the resolution only happened this May 2023. We went to court two times and we lost both times. This land issue actually lasted over a span of 4 Selangor “mentri besars” (chief ministers) including the infamous convicted former Selangor Mentri Besar Khir Toyo. He took the people’s land and built PKNS (Perbadanan Kemajuan Negeri Selangor) housing there but the people had letters, promissory notes and all that, but we still lost despite all the evidence. Anyway when Pakatan took over Selangor, we thought that was a good sign and thought we could finally have a chance to get the land. Moreover I was then the moderator of the urban poor special committee under the Selangor housing exco Iskandar, so I had a leg into the state government, and yet the case had remained unresolved. We finally decided to stage a protest action outside the SUK (Setiausaha Kerajaan) or State Secretariat building in Shah Alam but what did it achieve? The people who used to stand with us against the BN police and government became the people who tried to stop our actions, they closed the gate and made us wait and stand in the hot sun for a few hours.

After each protest action, we would make we had all the information and everything in dealing with the media. Another important thing was the documentation which would help us ensure different branches in the government knew about it. This meant different exco members, the MB, including even Anwar Ibrahim and different PH officials also had to know about this and the way our protest was handled by the State government. We made sure our close contacts in the PH would convey the incident to their bosses in the respective PH component parties. Some PH supporters had labelled us “pengkhianat (traitors) but we explained that this is the right of the people and they should pay close attention instead of being defensive and calling us names. We do not only organize a protest but we have to pay attention to many other things as well in following up certain actions. And before that, we had to build up towards the action so that protest becomes a very strategic tool. If not, your demonstration, mass action or peaceful protest would not be effective but just a shouting exercise.

Another example of a protest action is when we were made to wait for more than 6 hours when DBKL had agreed to a dialogue meeting with us with regards to the Jinjang Utara longhouse housing issue. So we decided to stage a creative protest, we had already gathered the press downstairs and so we walked out of the waiting room and met the press at the doorsteps of the DBKL. We dramatically tore up the invitation letter and explained to the media what had happened. The media covered it extensively and the Datuk Bandar himself immediately called us and issued an apology. We seized the opportunity to turn the situation around by challenging him to go to the ground and see for himself what had been happening in the community. A few days later he organized a small convoy of 5-6 vehicles with all the relevant city hall officials together with him, and the housing developer who had promised to build the low-cost housing. We took them around the area for 3 hours and after that things started moving and the developer started to restart the housing project. You see, a cleverly planned protest action can lead to positive development if we have a good step by step strategy.

The most important thing for our social movement is strategy. In order to have a good strategy, we need to analyse the situations sharply. Otherwise, we could be stuck because we did not identify the correct root cause or main player in an issue. If our analysis is inaccurate, we may not be able to plan and determine the type of protest action to organize, for instance to have a peaceful protest or confrontative one. It depends on what we want to do. We want to show our anger or we want to show that we are victims? If you are victims, you don’t go there and shout. You go there and look pitiful. These are some tricks, the point is we have to be clever.

Protest in SUK Selangor by PERMAS and Rawang rumah panjang residents to demand their promised land (2010).

What was your learning trajectory for acquiring all these strategies? How did you get to this point of understanding what should be done?

Like I said, we need to be very vigilant. We have to be very sensitive to absorb learning as we continue to be involved. This is not a game, It’s not a hobby, for us, it’s life. We made our life choices, I made my life choice, so it’s very real for us. Working with NGOs and in community organizing it does not really guarantee you a stable and regular paying job. In fact all those years, and even until today some of us still take from our own pockets to fund certain activities and actions. We were not paid salaries in those years

I studied and got involved in actions and activities in the Philippines for 7 years, and I learnt a lot from that experience. The Philippines movement is very creative, they use a lot of theatre in their mass protests. Groups like PETA (Philippine Educational Theater Association) and others were really good in making protest actions exciting and kept the people’s spirits up in long marches and protest actions which could stretch to a few days or even weeks. India, there were also many street theatre groups and very interesting ones. In Thailand we also have friends working in community theatre groups and using a lot of street theatres to highlight issues.

Another example was the Kampung Railway (Sentul) press conference of 1999. We decided to stage a drama skit instead of the usual talking speech making events. The community people staged a small drama on eviction in the open air space with everyone gathering round and the press sitting under the tent. Of course we had to prepare, but the point was just to do something different. The media loved it and gave us extensive coverage. Always explore creative and unusual approaches, use different tricks and skills in dealing with the media. Also good to have media campaigns skills and tools. Being an NGO person doesn’t mean you are just very good at protesting, it’s not enough. You need skills. If you don’t have skills, you are useless really. You need to be able to write well, communicate well, and be able to explain something in a very short manner. Dealing with the press, try to avoid numerous pages of writing, one page is enough. Don’t write lots of slogans, just state the facts

You mentioned mobilising not just the urban squatters themselves, but also the gangsters. How do you go about that and how are they involved in the process of movement building?

We have to be realistic. We live in a society, not everything is good and everybody is good. The circumstances force us to deal with different elements. We need the protection of say, gangsters. Among the gangsters that we worked with, some of have changed (for the better) quite a bit. But then some, they don’t change. I know that one of them was involved in some serious crime and was hiding from the police. I met him secretly I day and I scolded him, “What the hell are you thinking? You have a family..” But anyway, he settled it by paying his way out of that mess. But yeah, these things happen and we got to deal with that. Some of them change and others don’t but we have to deal with all of this.

If you’re talking about movement building, everybody is part of the movement. Like I said, don’t be so naive to think that all in government are bad, all businessmen are cruel, all community people are victims. No such thing. Sometimes, there are better people in the government than in the community. Sometimes, there are more understanding people among the business people than in the NGOs or community. For instance the Bakun Dam issue from 1994 till late 1990’s my colleague and I used to travel to Bakun quite often to support their efforts in organizing the communities against the destructive Bakun Dam which displaced 10,000 people in 14 communities. Anyway, I was blacklisted by the Sarawak immigration and was deported the first time from Kuching in 1999 and again in 2000. I had tried to go in but failed through the normal channels. But I was able to gain access through the forest routes after that, but it was very expensive, and long journey imagine from KL to Kuching took me through Sabah and after 3 flights, 6 taxis and 14 hours, I arrived in Kuching. The irony was the one who reported us to the Special Brance (SB) was a local ignorant boat man who thought his income was threatened if we stopped the dam. When our local Bakun community leaders found out about him they really gave it to him. And now because of him I cannot enter Sarawak for the past 30 years. So not all community people are good…

Another example was the Jinjang Utara longhouse issue. Three SBs used to tail us and followed all the public community meetings we held for 4-5 years. After some time we got to know them and somewhat became aquainted with each other. I didn’t try to hide the fact that there were police personnel present, so I would announce their presence and we never disrespected them. In fact I would provide them with a copy of our statement every time we had one. I knew that he had a task to perform and he had to report something and we had nothing to hide. Sometimes just to shake things up a bit we would just tell them we do not have the statement and cannot give them a copy. His name was also Tan so we had something in common. Sometimes we would engage in discussion and he would also ask me stuff about housing because he must have realized that all we did was deal with housing rights for the poor communities. Once he even asked me if I could help his relative who had a similar issue. They are also human after all and by building good relations with them we can have an ally when in times of need. That is why I say that we have to consider everybody, gangsters included if they can help you, fine.

There are also gangsters who have threatened to chop up our people before in the Batu Caves in those years in 1980s. We started an alternative committee there and then we ran kindergarten and stuff like that, so they didn’t like it. One night, they attacked our teachers and they chopped up some of them. We did not want to run away from the community because we were organizing the community so we contacted another gang leader who is more senior and arranged for a table talk and settled the issue, they had to pay medical fees and loss of income to those injured, and they promised not to disturb us again. But the damage was done, it took some time for the community to gain their confidence to gather for activities and meetings again.

Same thing happened in Berembang as well, right?

Many things happened in Berembang. But the thing is, when something like this happens the people themselves get scared and it is very hard to mobilise them again. They would be scared to come for a meeting again but you have to use other ways in dealing with things like this.

Another example was the Batu Arang estate “wildcat strike”. This was in the 1980s. This is a typical example of sometimes NGOS who are supposed to be comrades turned out to be worse than the government. We had been organizing the rubber estate for the past 1 year when things got heated and they decided to strike against the management’s treatment of them as contract workers and the bad working conditions. Suddenly, because of the wildcat strike, politicians and everybody come in. The issue became very hot and intense and everyone wanted to jump onto the band wagon. There was another group or several other individuals who actually came in and stayed in the estate and started to influence the workers with his own ideological views and controlling them. He managed to poison their thinking and when we approached the workers we were ignored by them. Later on, we thrashed out the matter in a NGO coalition meeting (quite rare in those days because it was hard to organize many NGOs meeting together due to security concerns). So what I am saying is that you can find enemies even among friends so we cannot be naive but in movement building you just have to know who is an enemy and who is a friend (“kenal siapa lawan, siapa kawan”).

Jo Hann at a protest by the National Union of Bank Employees (2012).

Can you walk us through one campaign you worked on from start to finish, either failure or success, just to illustrate the whole process?

The thing is it is very hard to say if there an ending or not. Because these are all life issues. But there can be certain periods where certain things have been achieved or done or not done, and it’s never like, successful or fail, it’s both. So the best example I can think of is this housing for the poor campaign. We actually looked at it as a campaign, it was such a lifelong campaign. Like I said, the Rawang land issue is 33 years old until today. It is only now (May 2023) that we have received news that they have got alternative land from the Selangor state government to replace the land that was taken by Khir Toyo long ago. Some of the landowners have already died. Their children are already adults with their own family, so ownership is passed to them. But anyway, for me, this kind of result shows us we have achieved something. At least some fruits of the labour came out of that campaign.

Another example would be in Jinjang Utara, being the biggest rumah panjang in Malaysia, with 8,000 people. For 30 over we have been struggling with them and finally, in 2020 they were offered low cost flats with a special price. They were evicted from the railway squatters in 1991-1992, and they had moved from along the railway tracks to this rumah panjang in Jinjang Utara. We have been accompanying and supporting them from that time until now. They were told then that they would only have to wait for 2 years and that the longhouse was a temporary settlement. Since then they had been waiting for 32 years. So again, that is another achievement lah I would say, the thousand over families.

When you deal with a community, even though you focus on housing, you have no choice but to deal with their family, their health, their education, their school, their children, everything. One of their sons got arrested for something we would have to arrange bail, free legal services and so forth. Some leaders have autistic children, so we also have to take care of their welfare. Single mothers, widows, we have to deal with all these so it’s not only a housing issue. These issues are sometimes endless, it’s their daily life and not a campaign. We have some gains but life goes on and they continue to deal with their issues deal with it every day. That’s their reality.

If you look at the Bakun campaign for example, although we were very intense and active in the campaign but at a certain point, it’s just a stalemate. If your campaign aim is to stop Bakun and at a certain point knowing that we could never stop it, then we adjust our demands, change your campaign strategy, and aims. And sometimes, people just lose interest. All NGOs have so many things to do, so many other campaigns, they jump from one to another sometimes. It’s really hard to pinpoint the beginning and end of a campaign.

If we take the housing for the poor campaign for instance, which has lasted over 30 over years, I would say the key there is to prepare the people to be empowered and skilled to fight for themselves. They will also feel that they cannot do it, but you have to be able to channel and pass on the skills to them. Skills, knowledge, information and certain way to do things. We have proven over and over again that people can do things for themselves. You cannot do it for people, because they will always be dependent on you. That’s the most important key. I can say that those communities that we worked with for the past 30 years can actually do things on their own, for instance they can hold meetings without the presence of people like me. For me, it is a good thing, you must know when to step out.

Passing on knowledge is one thing and the other important thing is to have a good strategy. Analysis and strategy are very important in any issue, any campaign. You got to understand the issue well. A lot of us are very good in rhetoric and slogans, but not really having a sharp or deep understanding of a certain issue. And when you have a wrong analysis or not a sharp analysis, your strategy will not correspond or will not address that particular issue. As you know in analysis, you have your root cause and your triggers. If you can identify the root cause, then you know where to hit and how to deal with the corresponding triggers. But if you see the triggers only and not identify the root cause, you will be off focus and your campaign will go haywire.

We are also looking at the idea of the protest space. Because you’re mostly working with urban squatters, so it’s very site-specific, encompassing urban villages, traditional villages and whatnot. Do you see such space as important to your work and does the space actually help with your process in visualising protests?

Are you talking about physical space?

Can be both the physical and the abstract.

I get what you’re trying to say, it’s like our right to spaces for instance in our fight to assemble in Dataran Merdeka. In a very simplistic way, it’s true. If we look at the issue of squatters, who are they really, Most of them have been on a certain area for 30, 40, 50 years when KL had just occupied a small area. Then communities of people started to occupy the areas at the fringe or outside the city which was then considered not part of the city. Then the city expanded and suddenly the government considered these communities “squatters” and say that they are encroaching the city spaces “illegally”. I should say that it is the city which had encroached upon the people’s land, so it’s not fair. That is why we prefer to use the term “urban pioneers” rather than “squatters”. These communities usually came from rural areas and if you trace the social history of Malaysia, the rural-urban migration had brought the people to the cities in search of jobs and better living.

Going further with this subject of spaces, I would even expand it to the government places. I always feel angry that government officers and civil service staff tries to chase public members from the premises as if it really belongs to them. But in fact these public spaces belong to the people. So who the hell are they to say that this is a government office, you cannot come in, you cannot do this, you cannot do that? That building belongs to the people, we paid money for it. For instance in DBKL and everywhere else we always had to contend with them when we go there to advocate our demands. Who are they to kick us out? They actually work for us so to use or occupy that kind of space is actually the right of the people. When do a peaceful demonstration in DBKL we often face lots of obstacles and so we use different strategies to gain entrance. We would go in one by one into the main hall pretending to come to DBKL to conduct some business. When we are all assembled, we would then take out the folded placards and start to shout in the hall shocking everyone especially the DBKL enforcement officers. Or when they have an open day to meet the clients, we go there pretending to seek the counter services. We have to do this kind of nonsense tricks just to get inside and their attention. When people say reclaiming your rights, it’s not literally like right to a physical space, it’s more of a symbolic space, representing our rights, our power, over something in our life. The space can be our house, government offices, and other items. Furthermore if they impose ridiculous and stupid dress code rules, it really maddens me, who are they to tell me which piece of clothing is considered not proper.

It’s very interesting when you mention how you are using different tactics to bring people into the offices.

Yes and we are not the first ones to do that. If you see all the protest action, sometimes you learn from others and how they do it. Different people do different things, not everything is correct. Depends on the time, the place. Sometimes, I don’t agree with certain protests also lah. Like for example, Greenpeace movement. Westerners sometimes have a different notion of protest and their style sometimes different from ours. For instance chaining themselves to the tree and so forth. I remember in the 1990’s some of them came to Malaysia and chained themselves to trees in Sarawak. At that moment, I felt it was not the right thing to do. So they got arrested and deported and then what? The locals are left to deal with the aftermath. But they got some good photos for their newsletters and claim they are supporting Sarawak anti logging? So ultimately the whole attention is about them and not the people and their struggles.

When you do a protest action, you make sure you do not obstruct the traffic, don’t block the walking path of the general public. Because if you become a nuisance to people then you lose their support. I just saw yesterday a video, these guys sit on the road in some western country protesting some road construction but they sat on the road and the truck drivers got really angry because they had to work and a schedule to keep. He got out of the truck and started roughly pulling the protestors from the road, throw away their signs and shouted at them for blocking the road. If you really want to protest the road building, occupy the local government city hall transportation or engineering departments.

In Kg Chubadak Tambahan, Sentul, in 1995 PERMAS together with the local community people once occupied the construction site which was built very close to the people’s community and created quite a lot of dirt, noise and harassment in the community. We went there, barricaded ourselves and kicked out all the workers. The police came, of course. It was just for a few hours, but it was symbolic and we didn’t hurt anybody. The Indonesian workers there were very scared, but we remained civil and friendly to them. We said no, we are not against you, you are only their workers. We put construction iron bars all around the area and when the police came we negotiated and it became a huge media thing.

Did the same thing happen after 2007? Did you use the same tactics?

After 2007, we didn’t do so much of that. There were other actions but not necessarily in the form of barricades, but we had many very heated confrontations as well in different places. Number one, it depends on how angry the people are. We don’t just simply go to a place and agitate the people to protest. It is usually part of a strategy of ongoing organizing process. In Kg. Chubadak, for instance the women were very strong, Kak Shida, Kak Wan and others. They knew the FT (Federal Territories) Minister’s representative was attending a meeting in the community organized by the local UMNO. So they decided to raid the meeting and take over the process to highlight their demands. We just supported with video and photo documentation and also to be there to support in all aspects. The atmosphere got really intense and everyone was shouting and there was shoving and pulling, and finally the government guy left. But we were still there especially to talk with the media people about the issue. The police came and the crowd dispersed. Some protest and confrontation actions are spontaneous and some are actually planned.

Sometimes we demo in the District Office. We don’t just go there and demo, we go there and say we want to see so and so. If they don’t allow us, we say we’ll sit here. Make sure you bring children. Sometimes children want to go to school, you say no, don’t go to school. Go to DBKL and make sure go inside. Then the mothers start pinching their children so children will mengamuk lah, (go amok) purposely make noise. Staff all panic and all crying, this and that. Eh, we want to see the pengarah for perumahan, ada ke? (Is the Director of Housing in…) They always say tak ada, mereka ada meeting di Putrajaya (He is not in, but in Putrajaya for a meeting) or something. But then we also have our agents, the sweepers and all. Some of them are our friends, some of them are from the community also. So the cleaning lady who happened to be one of our community members would go upstairs, and then come down to report “eh, dia bohong, ada orang di atas. (he is lying he is upstairs…), so we know the real situation.

Sometimes we make use of the media and press members who are sympathetic to our concerns to help us connect with certain government officials. If we asked to see that officer we would surely be refused but if a media member requests, they are a little more careful and usually would meet the media member. So we would convey our questions to the media person who could gain access to speaking with this officer and get his responses to our questions. Sometimes these tactics can be tiring and tedious.

In cases when we have already gained access to meet with a certain official, the next hurdle would be to push as many as possible to be part of the meeting. It is usually a negotiation process, and finally a number is agreed upon by both sides and then we proceed. But the general principle is not to go in alone. We teach the people different tricks to gain access and negotiate for all leaders to join the meetings.

In DBKL there was a high-ranking officer a deputy mayor Datuk S (not real name), he is really a handful. One time when we were protesting outside the DBKL, and after a few hours and fighting and shouting match between us and the police and the DBKL enforcement officers, we were finally allowed to go in to meet this guy. When we went in, he started scolding us like children, he shouted “Ini cara Malaysia kah, macam ini ada sopan kah?” (Is this the Malaysian way, is this the respectful way?) I could not take it and responded to him in a similarly hard manner, I asked him “Ini cara Malaysia kah, sopan kah Datuk melayani orang masyarakat seperti ini? You ada baca Perlembagaan Malaysia? Masyarakat ada hak untuk berkumpul” (Is this the Malaysian way, is it a respectful the way you treat members of the public like this. Have you actually read the Malaysian Federal Constitution which allows for the right to assembly?)

The officer together with his contingent of civil servant officers looked puzzled why I had cited the Federal Constitution, they kept very quiet. Among them, were several Special Branch police officers (SB) which was the standard practice when we organized protest actions in government premises. We usually ask everyone to introduce themselves so that we know exactly who were in the meeting and so they cannot hide under different covers. When empowering the people they have to actually see the process to be convinced and develop confidence in their confrontations with the police and government officials. We need to tilt the balance the power a bit in the people’s favour, be afraid.

We were going to ask if you think protests are effective but I think you clearly would agree that it is?

It really depends on how we use protest actions and why you use it. It’s too simplistic to say that if the people protest, it means somebody will listen to them. Its just a shout for attention, but after getting the attention, what you do next it’s important. You also need to know how to structure or design the protest, you have to be clear on your objectives. You need to use the protest moment to gain something, that’s why you protest. That’s my take.

Anything else you want to share, any final thoughts?

One thing is for sure that there are a lot of young people who are getting involved in social issues and social transformation processes, which is very good actually. Comparing those days, this is something that gives us hope. I mean, you guys are a testimony to that. Before, it was really hard to find young people to be involved in social issues because they are so concerned with all their studies and work and future.

But after having said that, I think having a strong foundation is very important. We cannot compromise on that. Getting involved, getting excited is one thing. But being committed and serious takes energy, effort, time and hard work. It’s not just excitement in attending protest actions and feeling very powerful marching in the streets like in the BERSIH rallies. You need to be committed, otherwise you will burn out after maybe 4 or 5 years. My message to young people is that it’s very good that they are involved, and have a good spirit. But you have to be serious and committed which means to acquire relevant perspectives, skills, knowledge and working hard for social change. We have to be very careful about this whole thing about protest, because people tend to see it as a glamorous, cool action. But that is just the start, the real work lies in the times in between the protests where our endurance is tested. If you really want to be part of the social movement, then this is it, and not spending one day standing under the hot sun and shouting slogans only.

Perhimpunan Protes Harga Minyak Naik at Stadium Kelana Jaya (2009).