- Introduction

Pengenalan - Transcript

Transkrip - Additional Resources

Rujukan Tambahan - Pictures

Gambar - Credits

Kredit

Drawing from intimate oral narratives, the fifth audio essay for the Suara ((( Pembangunan ))) project is produced by Yvonne Tan, entitled “Lost in Trilingualism”. This essay examines how language transmission—or its absence—shapes personal and collective identities across generations.

In foregrounding the complexities of linguistic inheritance within Malaysian Chinese communities, Yvonne’s experiences reflect a common struggle: growing up in Kuala Lumpur, she navigates a multilingual world where Cantonese, Hakka, Hokkien, Mandarin, Malay, and English converge.

Despite her Hokkien surname, her linguistic reality is shaped by the Cantonese-speaking environment of her childhood, her mother’s fading Hakka fluency, and her family’s prioritization of English as a means of social mobility. The essay sheds light on the layered negotiations taking place within families and institutions over which languages to retain, learn, or let go.

Tracing the forces of linguistic standardization, historical education policies like the Barnes and Fenn-Wu Reports as well as her own experiences through education, Yvonne questions what is left behind when a language ceases to be spoken and how development—often framed in economic or infrastructural terms—also manifests in cultural erasures. Through these narratives, her sonic essay asks: What does it mean to belong when the words to express it slip away?

Suara ((( Pembangunan ))) is a collaboration between Dr. Aizuddin Mohamed Anuar (Lecturer in Education, Keele University) and Zikri Rahman (Programme Coordinator, Pusat Sejarah Rakyat) and is funded by Faculty Research Fund (FRF) 2023-2024, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Keele University.

Yvonne: My parent’s generation communicates primarily via WhatsApp. Although they are literate in Bahasa Malaysia and English, they are not literate in Cantonese and Hakka. Their Whatsapp is always full of voice notes recording themselves and listening to the voice notes of their friends while sometimes resorting to typing in loosely romanised Cantonese or simply English or Malay. This is how my family navigates without knowing written “Chinese dialects”.

In Malaysian Chinese culture, you take on your father and paternal grandfather’s ethnicity. So I was always told I was Hokkien even though my extended and immediate family only knew Cantonese, which was the lingua franca of Malaysian Chinese living in Kuala Lumpur. Most of the food I ate was Hakka and Cantonese technically and I never really felt like I was Hokkien.

[Soundbyte: Restaurant in Kuala Lumpur with voices chatting sporadically, activity, and cooking by Soundsnap]

[Yvonne struggling to speak Cantonese]

Yvonne: mou yan tung ngo gong gwong fu wa, zo meh lei mou gao ngo (in Cantonese: nobody speaks with me in Cantonese, why didn’t you teach me?)

Mom: yan wei lei sai go, ba ba ma ma yi ging tong lei gong English (in Cantonese: because since you were young your parents talk to you in English)

Because English ho zhung you, Ing Man ho zhung you. (in Cantonese: because English is important, English is very important)

lei sai go hok dak fai, dai yong yu cap sau in school.(in Cantonese: since you are young you can learn fast later in school)

as you– lei jiong dai jo lei hai school, lei hai school you hok mah, zi gi hok loh (in Cantonese: now that you are grown in school you can learn (Cantonese) on your own)

Yvonne: Yi ga ngo mm dak tong ngo ge pang yao, tong ngo ge “relative”, dim mung gong “relative”? (in Cantonese: but now I speak with my friends, my relative, how do you say relative?)

Mom: Can chik (in Cantonese: Relative)

Yvonne: Ho do yan, kei dei how to say Chinese people? (in Cantonese: A lot of people, how to say Chinese people?)

Mom: Tong Yan (in Cantonese: Chinese people)

Yvonne: kei dei, gong ngo, wa ngo “banana”, mm sik gong. Ngo hou- (in Cantonese: they call me “banana” because I don’t know how to speak. I feel very-)

Mom: Kik Sam (in Cantonese: Hurt)

Yvonne: Mhmm Hai Kik Sam. (in Cantonese: Not hurt) How to say difficult?

Mom: Kan nan (in Cantonese: Difficult)

Yvonne: Ho Kan nan tong pang yao gong. Kei dei moi tung ngo gong. (in Cantonese: Difficult to be friends. They don’t want to speak with me.) So I’ve to be pang yao (in Cantonese: friend) with Indian and Malay people because they won’t make fun of me.

Mom: Oh that’s the problem. Because last time I didn’t know that I thought you can learn from school. That’s what your father said. You dad said you can learn from school so since childhood you already speak English.

Yvonne: So last time people teach you in school is it so you think other people will teach me?

Yvonne: My name, Tan Yit Fong, is technically bilingual which is rare for someone of the newer generation. With a Hokkien surname “Tan” and Cantonese name “Yit Fong”. Again, representative of my father’s side, with my paternal grandmother being Cantonese. With so much emphasis on following my father’s side, later in life I realised I know nothing about being Hakka. I just know we are called “guest people” and my mother can’t really recall where her mother or grandmother was from. We technically have no land to return to, unlike Hokkien being Fuzhou and Cantonese being Guangdong. With so many languages to learn, the shift of which “Chinese dialects”, Hokkien, Hakka or Cantonese were to be taught to me instead became conversations on whether to learn Mandarin or not which was important to achieving a unified language among Malaysian Chinese. With my parents themselves not knowing Mandarin, they decided not to send me to a Chinese primary school. But they gave me a Chinese name, a Mandarin Chinese name, Chen Yue Fang.

Yvonne: Can you teach me some Hakka? How to say “My name is Yvonne”?

Mom: Nga miang hem zo Yvonne ah. (in Hakka)

Yvonne: Nga miang?

Mom: Nga miang

Yvonne: Nga miang an zo?

Mom: hem zo, hem zo Yvonne

Yvonne: hem zo Yvonne. I stay in Kuala Lumpur, how to say?

Mom: Ngai hoi Kolumpo chu.

Yvonne: Ngai hai?

Mom: Ngai hoi Kolumpo chu.

Yvonne: Is there anything you remember in Hakka that sticks in your mind?

Mom: Sik fan (in Cantonese: Dinner). Sit Fan (in Hakka: Dinner).

Yvonne: Anything else? Nothing else? Only sit fan? Because always eat together? Do you still remember how to speak or are you forgetting?

Mom: Yeah because my mom passed away already. I don’t really speak Hakka anymore so tends to forget (laughs).

Yvonne: Do you remember anything your parents always say to you or your brothers say to you in Hakka? What do they normally say when they come home from work?

Mom: When my dad come home from work, when we have dinner, we will always have a very quiet dinner. My dad will not allow–my dad has 5 children, 4 boys and 1 girl. I am the only girl. When we have our dinner we are not allowed to talk. So when I talk he will say in Hakka “Sit nia fan, Gong gan do. Sit bao zhan gong.” Meaning means in English, “Don’t talk so much, eat your food first. Finish only you can talk”.

Yvonne: What does he say afterwards? Nothing?

Mom: No, after finish, then we already keep quiet so we do not talk.

Yvonne: The Barnes’ report in 1951 suggested the government should unify schools with Malay or English as the main language, while Chinese and Tamil would be taught as subjects. This suggestion was eventually incorporated in the Education Ordinance of 1952. That same year in 1951, the Fenn-Wu report was submitted. William P. Fenn was the associate executive secretary of the board of trustees for a number of institutions of higher learning in China. He and Wu Teh-yao, then an official at the United Nations, were invited by the federal government to conduct a study of Chinese schools in Malaya. This study became the Fenn-Wu report. It was critical of the Barnes report and advocated for Chinese as a cultural language, promoting trilingualism: Mandarin Chinese

On my maternal side, this shift to Mandarin Chinese was more clear. My mother was the last person educated in English as the main medium of instruction before national secondary schools moved to Malay in the 1970s. My grandparents decided to send my younger uncles to Chinese-medium schools. And by the 80s, the Selangor Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry launched the Speak Mandarin Campaign in Malaysia that ran from 1980 and 1985, following the Singaporean government’s own campaign launched in 1979. This trend carried on to my cousins who went to a vernacular Chinese school at primary level and eventually went to a national secondary school, thus becoming trilingual as the Fenn-Wu Report suggested while I remained a banana as my mother is. On my father’s side, on the other hand, preoccupied by poverty with few having the chance to have an education did not experience this jarring split between “Chinese dialect” and “Mandarin Chinese” within their family like my maternal side did.

Yvonne: So how do you feel, after you, nobody knows how to speak Hakka already. My cousins Sophia, Janna then me, we also all don’t know how to speak Hakka.

Mom: Yeah. it is not that important, Hakka, that you really must speak. That’s why, like I told you in KL city, everybody speaks Cantonese. Everybody knows how to speak Cantonese. Only when if you go to Penang, Johor, they all speak Hokkien. So most important you speak Cantonese is enough, you don’t need to know Hakka.

With my mother being the last person to know Hakka within my family, and her feeling there is no need to pass it down to me, given that she has raised me consciously to only speak English, I am not too sure how to feel about it. It would be too laborious for her to orally teach me Hakka from scratch. She learnt Cantonese to speak to my father, who did not know Hakka. Growing up, the Cantonese I learnt from my parents represented a different world from the Cantonese I watched in Hong Kong Cinema and in TVB drama series. And in both languages they don’t know what the word “development” is.

[Soundbyte: Traffic in Kuala Lumpur at a Chinatown intersection on a 4-lane boulevard, wet and thick gridlock, crawling with horns and distant whistles by Soundsnap]

1.Taming Babel: Language in the Making of Malaysia by Rachel Leow (2016)

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316563007

2. Language Planning for Modernization: The Case of Indonesian and Malaysian by Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana (1976)

3. On Not Speaking Chinese Living Between Asia and the West by Ien Ang (2001)

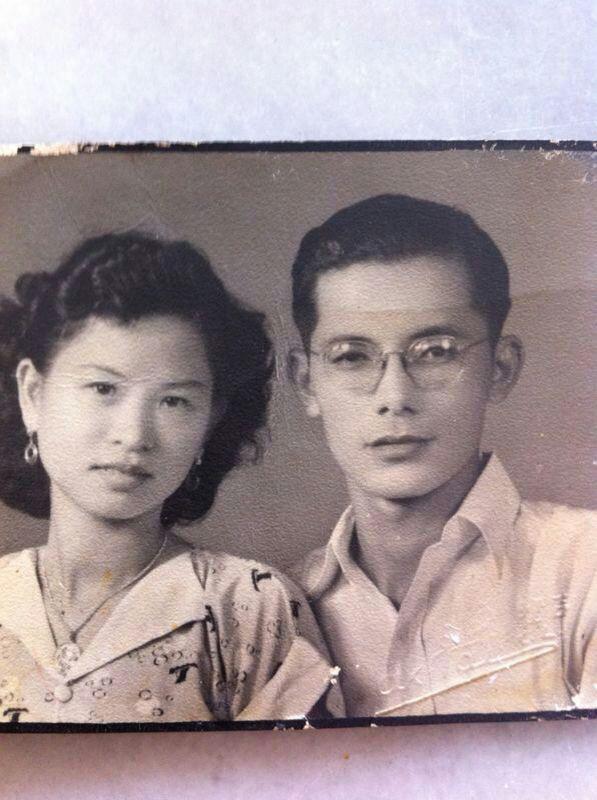

Yvonne’s grandparents Chan Sai Moi and Lee Chan Yew, who were culturally Hakka though Yvonne “never really felt like I was Hakka” as a result of negotiating trilingualism.

Credits:

Episode created, written, produced, and edited by Yvonne Tan

Voices:

Narrator and Inner monologue: Yvonne Tan

Mom: Lee Yoke Lan

Music and Sounds:

1.Restaurant in Kuala Lumpur with voices chatting sporadically, activity, and cooking by Soundsnap:

2.Traffic in Kuala Lumpur at a Chinatown intersection on a 4-lane boulevard, wet and thick gridlock, crawling with horns and distant whistles by Soundsnap: