By Koh Kay Yew (Activist, author and one of the board directors of Pusat Sejarah Rakyat)

Foreword

Tan Jing Quee was a key student leader during the critical ‘Battle for Merger’ in the 60s when he chaired the public forum ‘Basis of Merger’ where the split between the PAP leadership with the Left became public. Though he was made Assistant Secretary-General of Singapore Association of Trade Unions (SATU) after graduation in May 63 in spite of his youth, his detention several months later after the general strike aborted any lasting role. Jing Quee’s real historical contribution was two-fold:

A) He broke the ‘code of silence’ that engulfed ex-political detainees’ recollection of their experiences and past history through pioneering alternative narratives that challenged ‘The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew’ by Lee Kuan Yew with the publication of ‘Comet in our Sky: Lim Chin Siong in History’ jointly launched with Said Zahari’s political memoir entitled ‘Dark Clouds at Dawn’ in Kuala Lumpur (not Singapore). His keen eye for history was also reflected in the many eulogies/obituaries he composed for old friends/comrades who passed away, some prematurely, and holding memorial services in their honor;

B) As one of the rare English educated Left intellectual who was effectively trilingual ( the others were mostly Chinese educated), Jing Quee was among the last of our generation in Singapore to cherish the dream of a United Malaya including Singapore. It was reflected in his tireless road journeys up and down the peninsula to find and meet old and new friends and comrades, to garner their oral testimonies of past struggles. The tragic loss of his eyesight hobbled and handicapped his quest to unearth and consolidate the fragmented and untold history of the Left in Malaya. It was pure human will that enabled him to complete ‘The Fajar Generation’ and ‘May 13’ in the last years of his life. Other projects in the pipeline died with him, locked away in his tapes/files.

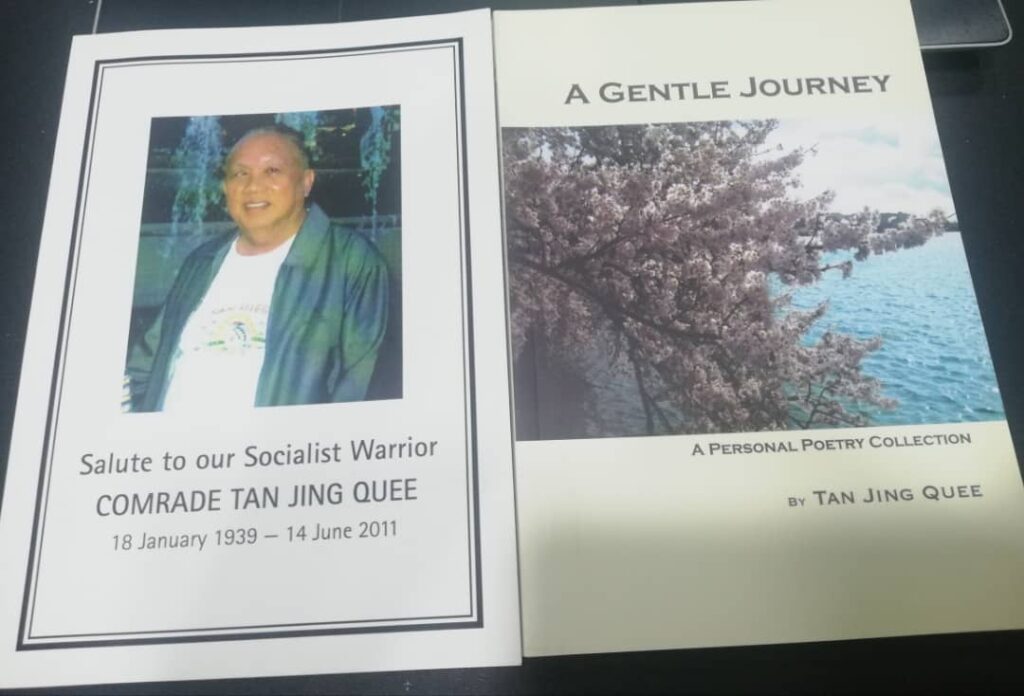

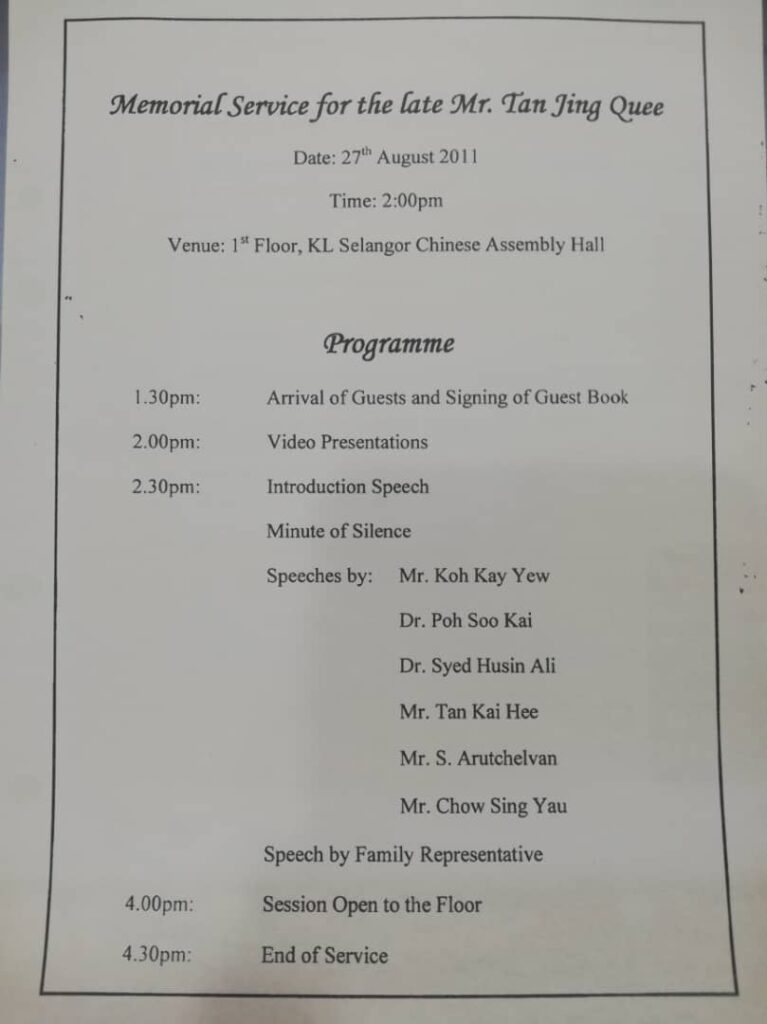

After his death in June 2011, Function 8 and others published a memorial booklet on his life. A lengthy piece I crafted in memory of my dear soulmate and old comrade was omitted due to attempted censorship of my passing reference to comrades who have ‘turned over’ like Fong Swee Suan but towards whom Jing Quee kept his friendship in his spirit of universal humanity.

In Memory of Tan Jing Quee

History is replete with examples of courageous men and women in different periods and places who even in their darkest hour are willing to subordinate their private selfish interests by using their talents to the greater good of society.

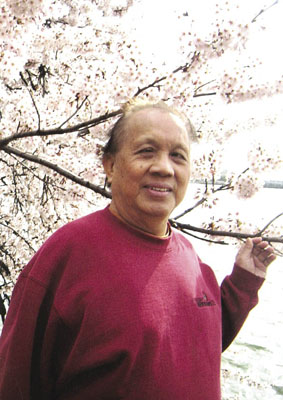

The late T.T. Rajah, in one of his rare compliments, described Tan Jing Quee as a ‘man of integrity’. At critical junctures in his life when faced with the choice between the wide, easy road of comfort and compromise and the long winding road of struggle and sacrifice, Jing Quee chose the latter.

Best known for his cutting edge leadership of the University Socialist Club in the critical early sixties when Singapore was at its political crossroads he together with Wong Kum Poh and R. Joethy spearheaded the opposition to the terms offered to Singapore for Merger and Malaysia.

Operation Cold Store in February 1963 signaled the resumption of State repression against the Leftwing-led mass movement in Singapore, but it did not deter him from joining the trade unions upon graduation in May that year. He was appointed paid secretary to Singapore Business Houses Employees’ Union and Honorary Assistant Secretary-General of Singapore Association of Trade Unions (SATU) despite being a novice to the labor movement. In response to the general strike called by SATU in protest against the deregistration of its three largest unions in October 1963, the PAP government detained him and other union officials.

After his release in late 1966 he could have, like others, returned to bourgeois life but chose to decline offers of employment from P.S.Raman, then Head of Singapore Radio Television Singapore, and from Kuok Brothers through Goh Soo Siah. Though he disliked law as a discipline he left for London to study at Lincoln’s Inn as law offered him the only means of an independent livelihood. He declined an offer of financial assistance from A.P.Rajah, then Singapore High Commissioner for the U.K., and struggled to make ends meet by living in a bedsitter in Earl’s Court with shared bathrooms. Material hardships were offset by newfound relationships as it was here that he met his wife Rose who was his neighbor.

London in the late sixties was in the throes of the youth revolt caught in the vortex of the Vietnam War, American civil rights struggle, the rise of Black Power, and the Chinese Cultural Revolution. It was vital for Jing Quee’s revival after his prison travails. In 1969 Lim Chin Siong arrived in London accompanied by Dr. Paul Ngui of Woodbridge Hospital following his mental depression in prison and release. They were accosted by Jing Quee and S. Ghouse who successfully demanded that Lim be handed over to their care. In the months that followed they helped nursed their fallen leader slowly back to mental health. One is tempted to speculate on the fate of Lim had this intervention not occur.

After his graduation in law and return home, Jing Quee joined Rose in nuptial bliss in 1970. He joined Lim Chin Joo in 1973 in a new legal practice that became one of the most successful local law firms on the island. As Chin Joo was well known in the Chinese community and could have his pick of partners, Jing Quee believed that the partnership was extended to him in reciprocity for the help he gave to the elder brother in difficult times. Law was to give the reluctant lawyer the financial sinews in later life to pursue other interests closer to his heart and to provide unstinting support to many other comrades and friends whose loved ones were facing hardships due to the detention of their breadwinners.

Jing Quee was quintessentially a humanitarian who firmly believed in universal humanity. It was this deep wellspring that led him to embrace the Socialist credo that human society should be organized for the benefit of people, not profits, for the service of the working majority who are dispossessed and not the exploiting minority who are the owners of capital, and for national and not alien interests. His magnanimity of spirit manifested itself equally in his reluctance to pass judgment even on comrades who had ‘turnover’. He maintained his friendship with Fong Swee Suan. His recent obituary on Soon Loh Boon is of the same genre.

From 1980 till the mid-nineties, Jing Quee was often found in the company of Said Zahari who was released in 1981, A. Mahadeva, and Lim Chin Siong who returned home in 1979. One could say the four friends formed a defacto multi-racial leadership caucus of the defeated Left. On an unexpected encounter with Dr. Lee Siew Choh one day, the latter remarked: “Are you all still meeting each other?” In 1989 they watched with quiet anticipation on television in their hotel room in Tanjong Pinang the historic peace accord being signed in Haadyai between the MCP, Malaysian and Thai governments.

Lim passed away in February 1996. Said Zahari moved to Kuala Lumpur with his family not long after. A. Mahadeva also passed away in 2005. With the demise of his closest group of friends, Jing Quee moved closer to the Chinese educated ex-political detainees of the sixties. A mutual friend had observed that his Mandarin had improved significantly in recent years.

After his early retirement from his law practice in 1998 partly due to his failing vision, Jing Quee devoted his life to an intense study of the marginalized history of the defeated Leftwing movement in Malaya and Singapore and attended academic talks and seminars organized by ISEAs and others at home and abroad. He maintained his interest in the international Left movement and China.

Though he was imprisoned for three years without trial by the PAP government for his alleged engagement in Communist United front activities it is noteworthy that in his last book ‘May 13 Generation’, he used bourgeois scholars like Benedict Anderson and James Furnivall as his benchmarks of ‘the Nation’ not Lenin and Stalin’s famous tracts on the National Question! Throughout his life, he was acutely conscious of the complex web of ties that bounded Singapore and Malaysia and nursed the hope that a closer relationship may prevail at some distant future date. At the personal level, he built extensive relationships with activists that spanned both the racial and generation divide on both sides of the causeway. We were the last of our generation to organize events on a pan Malayan basis. Unlike his English educated peers, he was trilingual in English, Mandarin, and Malay in appreciation of the region we lived in.

The ‘May 13 Generation’ and ‘Mighty Wave’ were his last effort in print concluded despite his blindness and cancer-stricken condition. They recognized the huge sacrifices and sufferings endured by the Chinese educated in pursuit of the idealism of their youth which has been demonized in the official history of Singapore though it was with their support and that of the Middle Road trade unions that the PAP was born in 1954 and self-government attained in 1959. Together with the Fajar sedition trial in the same year, May 13 was the catalyst that ignited Singapore’s anti-colonial struggle.

Jing Quee was the first ex-political detainee to break the decades of silence that entombed the sacrifices and sufferings endured by thousands of political detainees in Singapore when he spoke on their experiences behind bars at a public forum on “Detention, Writing, Healing” organized by the Singapore Arts Festival in 2006. At the turn of the century when the National Museum expanded their coverage of Singapore’s anti-colonial struggle through the ‘balanced’ inclusion of Lim Chin Siong, they interviewed Jing Quee and Dr. Lim Hock Siew but their views were edited to one minute each with twenty or more minutes devoted to Fong Swee Suan’s version of Lim and that period.

As a man of the arts and letters, Jing Quee eloquently captured many of his intense moments and feelings with sensitivity and passion in the poems that he crafted through various stages of his life. They are a priceless heritage of man and his historical times through the journey of Life.

Tan Jing Quee was not a towering figure in Singapore’s anti-colonial struggle nor was he one of the ten tall men of the Middle Road trade union movement. He also did not languish in prison without trial for decades. He was one of the youngest leaders of that generation of young men and women who gave the prime of their lives in pursuit of their ideals. Our proximity to him in life has detracted his greatness that only a posthumous appreciation is possible. His real historical value laid in his quiet but relentless challenge to the victor’s version of Singapore’s formative years in spite of his physical handicaps through to the last days of his life. Living in the lion’s lair, his second detention in 1977 taught him that the limits of what he could attempt to do were determined by the State and not by any adventurist aspirations. Though he did not live long enough to witness any Singapore Spring he saw the sea change in public sentiments towards an oppressive State and helped drive the wedge for democratic space with the publication of his last two books, the Fajar Generation and May 13 Generation, two sides of the same coin.

We can best honor his memory by continuing with what he valiantly strove to do even though his premature departure denied him the realization of many other projects he had in mind. He will always be remembered for his intense engagement with the historical process and the inter-connection of all social phenomena based on the Hegelian dictum: ‘The Truth is the Whole’.

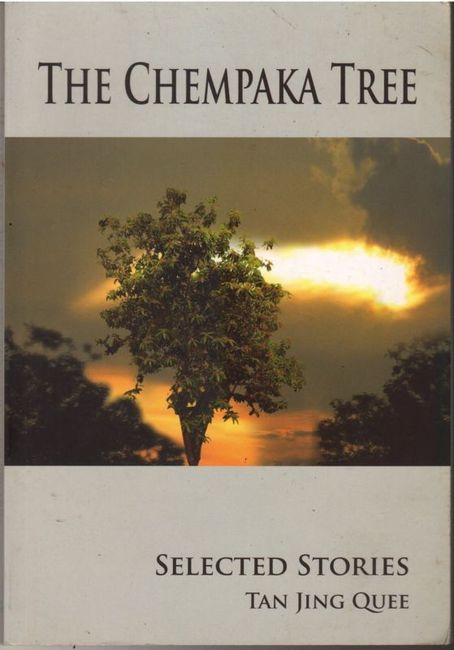

Tan Jing Quee’s Selected Literary Writings:

Selected commemorative articles on Tan Jing Quee:

- Tan Jing Quee (1939-2011): setting new directions in Singapore studies by s/pores

- TAN JING QUEE (18 January 1939 – 14 June 2011) by Hong Lysa

- TAN JING QUEE (18 Jan 1939 – 14 June 2011) by Teo Soh Lung

- Tan Jing Quee – A Man of Letters by Dr. G Raman